Tuna is an important global business, as well as a critical source of both protein and livelihoods for many around the globe. Therefore, it is critical that they are effectively and sustainably managed. Five Regional Fisheries Management Organizations (RFMOs) are charged with that responsibility, overseeing tuna fisheries management in their respective regions that collectively cover over 90% of the ocean.

RFMOs have members from developed and developing nations and manage a wide range of gear types that harvest tuna in areas both under national jurisdiction and on the high seas. Therefore, it’s no surprise that agreeing on how to manage these critical stocks can be challenging. It is crucial that the rules for managing tuna stocks are well-defined and agreed in advance, providing a prescriptive, proactive roadmap that directs management action. That’s where pre-agreed frameworks called harvest strategies, sometimes referred to as management procedures, come in.

But what exactly is meant by “harvest strategies?” And how can fisheries managers, members of the supply chain and seafood consumers tell if RFMOs are making progress in adopting and implementing these key measures?

To answer these questions, the NGO Tuna Forum, a collaboration of more than 30 NGOs engaged in global tuna sustainability efforts, has developed a methodology to evaluate which RFMOs have adopted and implemented harvest strategies for the stocks they manage, as well as to track their progress over time. The result is our RFMO Harvest Strategies Assessment Tool.

The intent of this tool is not to rate or rank RFMO efforts to manage tuna stocks. Rather it is intended to show where progress is being made and highlight where more work is needed. It also serves as a resource for all engaged stakeholders to better understand where we are in the shared journey toward adopting and implementing harvest strategies to achieve effective tuna stock management.

The tool spotlights the nine elements that participants in the NGO Tuna Forum have defined as the components of comprehensive, precautionary harvest strategies that must be collectively adopted and implemented by the RFMOs. They are:

Definitions and scoring criteria for each element are included in the assessment methodology.

The tool allows users to view the current status of adoption and implementation of each element of harvest strategies for each tuna stock by RFMO, as well as allowing a view of current status of each tuna stock across all RFMOs. The tool is updated twice a year to reflect the latest RFMO actions. Again, the goal is to provide a clear understanding of current status, recent progress, and areas where further progress is most needed.

We believe having a single set of benchmarks of clearly defined elements of harvest strategies, which anyone can use to track RFMO progress, is vital for advancing the adoption and implementation of harvest strategies, which are the most effective path to long-term, sustainable tuna management. Stay tuned to the tool to see what progress the tRFMOs make this year toward the NGO Tuna Forum’s 2024 harvest strategy-related policy asks!

Robin Teets is Project Lead for the NGO Tuna Forum, an independently coordinated and funded body of more than 30 NGOs that work comprehensively on tuna sustainability issues globally.

Small pelagic fishes, like sauries, mackerels and sardines, are sought after as important sources of fish oil and food for both humans and domestic animals. They also play a critical role in the well-being of their ecosystems as prey for a variety of species, including commercially important tunas and billfish.

These so-called forage fishes also share characteristics that pose unique challenges for fisheries managers trying to maintain their stocks at healthy levels: being short-lived, fast-growing and more susceptible to changes in their environment. These characteristics can lead to boom-and-bust cycles for some small pelagic fishes.

The bottom line is that traditional fisheries management can struggle to reduce fishing pressure quickly enough when necessary to avoid crashes of these stocks.

Avoiding such a dire situation is one reason the management procedure (MP) approach increasingly is being applied to the management of small pelagic fishes. The South African anchovy and sardine fishery was one of the first small pelagic fisheries to be managed through an MP, having been first implemented in 1994. Although in more recent years, declarations of exceptional circumstances have triggered temporary suspensions of the MPs, the management procedure approach is credited with the setting of catch levels without long and contentious debates. More recently and to the north, the mostly French- and Spanish- fished Bay of Biscay anchovy population collapsed in 2005. Development of a management procedure is credited with rebuilding the population while allowing an economically viable fishery.

By setting rules for fisheries management in advance and testing those rules against a range of plausible scenarios, fisheries managers can set up a system that has the potential to react quickly when changes in stock size are detected.

Although MPs, also called harvest strategies, have been more widely adopted in tuna fisheries, starting with southern bluefin tuna, they can be just as useful in maintaining stocks of small pelagic fishes. Management procedures are being developed for small pelagic fishes across the Pacific.

Members of the South Pacific Regional Fisheries Management Organisation (SPRFMO) are developing operating models to support management strategy evaluation (MSE) of jack mackerel, the RFMO’s most important finfish resource. Although development of the management procedure has been underway for some time, substantial progress is possible this year. It is critical for members to start suggesting options for MPs, including harvest control rules for testing.

In the north Pacific, the North Pacific Fisheries Commission (NPFC) is scheduled to take a significant step forward at its annual meeting that begins April 15. It is scheduled to adopt an interim harvest control rule that prioritizes the recovery of Pacific saury, which has been overfished for years.

A dialogue group of scientists, managers and stakeholders narrowed a range of options to four that have been simulation tested. All are predicted to recover the stock to BMSY within the time frame desired. Japan has proposed amending the Pacific saury conservation and management measure to implement the management objectives and HCR form agreed from the dialogue group. One consideration, however, will be the degree to which the HCR can adjust catch from year to year. The options included a constraint on the maximum allowable change in catch from year to year of 10, 20 and 40 percent, plus a fourth option that avoids a catch reduction in year one of the HCR and then allows the HCR to set catch levels without a stability constraint being applied. Members will decide on those elements at their Commission meeting this month.

Tightly constraining the allowable change in catch (i.e., the 10% option) brings greater interannual stability to the fishery but delays rebuilding and reduces the ability of the HCR to reduce or increase catch levels in response to changes in the biomass of saury, which potentially allows catch to remain above sustainable levels if the biomass declines.

Importantly, once NPFC adopts an interim HCR later this month, it must continue its work to develop a full, MSE -tested management procedure that includes longer-term objectives for the stock and considers the species’s critical role in the ecosystem.

It’s refreshing to see NPFC, a young RFMO, making relatively quick progress to improve the collective management of this important small pelagic fish, and hopefully many other NPFC stocks in the future. In contrast, a handful of others, such as the North-East Atlantic Fisheries Commission (NEAFC), should take note that they are quickly falling behind the likes of NPFC, where the use of a dialogue group facilitated agreement on shared objectives and a commitment to the management procedure approach has resulted in progress. In NEAFC, the principal challenge for similar progress appears not to be with the science but firmly in the hands of fisheries managers and decision-makers who are frozen by allocation disputes, lumbered by inefficient governance systems, and stuck with the traditional short-term fisheries management approaches.

NPFC and SPRFMO are proof that progress can be made in the development of MPs for internationally managed small pelagic fisheries. All it takes is willpower, time and investment. In April, we hope NPFC secures its first interim HCR that will recover saury, pave the way for a full management procedure and demonstrate to the other RFMOs that NPFC is in business and ready to lead from the front. And we hope that the other RFMOs take note.

Author——————————-

Steven Adolf

Senior Consultant – Sustainable Fisheries and Ocean Management

Author of “Tuna Wars”

✉️

The Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) is the most reliable certification organization when it comes to setting a standard for sustainable fisheries and a sustainable supply chain. But with the recent postponement of a number of announced measures around the new Standard 3.0 and harvest strategies, the certification body seems to have crossed the boundaries of transparent and inclusive management of fishery stocks. The review and delay of new fishery standards has resulted in a confusing patchwork of measures and timelines where even specialists like the certifiers and certified stakeholders seem to be lost in translation. But what really pushes the certification beyond its limits is the unilateral decision to leave out the usual consultation of all stakeholders. This undermines an essential part that brings trust and independence for the MSC certification and fails to advance the implementation of the substantive policy improvements intended under Standard 3.0. It raises the question whether the MSC certification must rethink its use as an effective tool to guarantee its Principle 1 of sustainable management of the fisheries, in particular on harvest strategies.

In an announcement on its website on January 31st, MSC published a set of delays of its new Standard 3.0. ‘We desperately need a MSC for Dummies to really understand it’, commented a market stakeholder and well-informed frontrunner on sustainable tuna management. ‘This is getting very complicated’, another specialist commented. Precisely at a time when sustainability policies need to be adapted to clarify the rapidly changing demands and requirements in the sector, MSC certification is taking a course that is difficult to follow, even for specialists who are directly involved.

According to the announcement, MSC has delayed the implementation of the long-awaited Standard version 3.0, that went into force in May 2023, for 2-3 years. According to MSC: ‘We have engaged in an intensive roll-out program, testing the new requirements with fisheries and gathering extensive feedback from independent assessors and fishery partners at workshops held around the world. This process has highlighted areas that need to be amended.’

It remains a matter of conjecture what exactly the problems were, or the scope of the issues, or how the MSC will ‘fix’ them, but the shortcomings were serious enough to warrant a postponement of the new standard. On the other hand, being ‘non-substantive changes’, the issues apparently were not that serious to involve other stakeholders in another public consultation process. According to MSC that would only cause more delay.

But the ‘no more delay’ argument seems to evaporate in the rest of the course of events. The derogation of the Standard 3.0 started in February 2024, and the release of an updated standard that will address immediate concerns is planned for July 2024. The old Standard 2.0 can be used another two years until February 1, 2026 for new fisheries, while existing fisheries have until 1 November 2030 for the update to Standard 3.0. This also extends the harvest strategy development and implementation deadlines for both new and currently certified fisheries, delaying some of the improvements of new standard and potentially leading to a loss of motivation to make progress on harvest strategies at the regional fisheries management organizations (RFMOs).

The process of developing Standard 3.0 was long and difficult and involved lots of fighting and mixed reaction, especially in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean (WCPO). This was in part due to the addition of so-called Section SE for RFMO-managed fisheries, which sets 5-year versus 10-year timelines for harvest strategies development that nobody is entirely sure how to interpret. But these can be considered political trade-offs for a reform of the standard that in the end enhances the implementation of harvest strategies in RFMOs, a key tool to bring fisheries management to a state-of-the-art level. By nature, this is not only a complicated technical process, but also part of ‘Tuna Wars’: important conflicting global interests of the involved stakeholders. Approximately 60 percent of the world supply of skipjack, yellowfin, bigeye and albacore is caught in this part of the Pacific. And a substantial portion is MSC certified. This multi-billion market accounts for 43 fisheries including powerful stakeholders on a global scale like the Parties to the Nauru Agreement (PNA) – the tuna power bloc of seven Island States in the WCPO – and Tri Marine, AGAC, Silla, and PNG FIA. In the last decade, the WCPO tuna fishery was the fastest expanding in MSC certification.

Within such a complex context, it is important that the final outcome of a revision of the MSC standard is supported by stakeholders, whether they represent the coastal states, fisheries, trade, science or NGOs. You don’t necessarily have to agree with the overall end-result if you know that your objections and suggestions have been heard and balanced with those of other stakeholders. A traditionally transparent and accountable consultation process is perhaps the most important reason why MSC can be considered a benchmark of sustainability certification.

And yet precisely this part of the process is being skipped in the new revision and delay for the introduction of the very important Standard 3.0. The concerns that had apparently arisen with the ‘independent assessors and fishery partners’ remain an enigma to other stakeholders. In particular, MSC should be extremely cautious to create an impression of a closed meeting that leaves the decision in the hands of fisheries interests. Possible time savings do not outweigh the breaking of one of the principles that form the backbone of confidence in the certification, a confidence that has been waning in recent years. Maybe the amendments on Version 3.0 that are now discussed can bring some simplicity in the current situation around the harvest strategy implementation, but there is no indication that the revision will touch Section SE. Regardless, it comes at too high a price.

The course of events surrounding the new standard and harvest strategies also means that a deeper, fundamental question must be asked. Up to what point can the MSC certification be a useful, transparent and inclusive instrument and indicator of progress and change toward more sustainable fisheries? MSC is meant to be a tool to serve the Theory of Change, using market demand to steer the management of fisheries into progress for a sustainable future. The Standard is supposed to work as an incentive to bring fishing into more sustainable waters instead of creating a maze of regulations in which even relatively well-managed fisheries become entangled in complex conditions, arbitrary time frames and non-transparent delays.

MSC is treading on dangerous ground for its credibility by taking unilateral action without proper stakeholder engagement, in combination with delaying essential parts of the Standard 3.0. That can never be the intention of a certification that claims to advance the proper introduction of harvest strategies. It’s a good moment to reconsider.

Steven Adolf is a researcher and consultant regarding sustainable fisheries, and author of ‘Tuna Wars’, www.tunawars.net.

Author——————————-

Hilario Murua

Senior Scientist, International Seafood Sustainability Foundation (ISSF)

✉️

With 4.8 million tonnes caught annually, tuna are one of the world’s most popular and nutritious seafood species, fundamental to global food security and serving as an economic engine for many coastal communities. It is essential that the regional fisheries management organizations (RFMOs), charged with overseeing the world’s tuna fisheries, identify and implement tools for the long-term, sustainable management of global tuna resources.

Harvest strategies, also known as management procedures, are one such proven tool available to RFMOs. Yet these management frameworks are in place for only a handful of the 23 commercial tuna stocks. ISSF continues to advocate that tuna RFMOs establish harvest strategies for more tuna stocks—because closing this gap will help fisheries managers mitigate both the political pressures andclimate change impacts on global fisheries.

Understanding Harvest Strategies in Tuna Fisheries

Harvest strategies are a combination of monitoring, assessment, harvest control rules, and management actions designed to meet the stated objectives of a fishery. These elements together provide a pre-agreed approach for RFMOs to manage fisheries resources in a transparent, inclusive, and precautionary manner, allowing management actions to be adjusted automatically in response to changing tuna stock status indicators. For example, if an indicator shows an increase in abundance, the management response can be to increase the total allowable catch, and vice versa.

With harvest strategies in place, fisheries managers can address any “what if” scenario that arises regarding the biology and productivity of the tuna population or other characteristics of the fisheries. These strategies also can account for uncertainty related to biological factors, such as fish population growth and natural mortality. (See this infographic for a visual explanation.)

Most important, without harvest strategies, short-term objectives of RFMO-member nations that may not align to scientific advice—continuation of catches at too-high levels, for example—can hijack tuna RFMO negotiations. And the result can be a further worsening of stock status and failure to ensure long-term stock sustainability.

Because long-term management objectives are pre-agreed as part of harvest strategies, decision makers can transcend short-term concessions that tend to be political in nature—a common phenomenon in multi-stakeholder, multi-national processes like global fisheries management.

The Impact of Climate Change on Tuna Fisheries

It is widely accepted that harvest strategies are crucial to achieving sustainable and profitable tuna fisheries, and to meeting and maintaining critical sustainability standard certifications.

With sustainable management long into the future as our goal, it is also important to understand how harvest strategies can help tuna fisheries weather the impacts of climate change. Let’s first consider how it is affecting global tuna stocks, and then how harvest strategies can help mitigate such affects.

For tuna and other fisheries, scientific studies suggest that ocean temperatures will continue to increase due to climate change, impacting fish stock migration patterns, distribution, and productivity. Climate change also affects other species in marine ecosystems, and it changes ocean currents and oxygen levels. With less resilient fish stocks and shifts in tuna populations’ geographical distribution, fleet competition, access to resources, and fishing pressure may be exacerbated. And that scenario, in turn, has the potential to disrupt tuna-dependent economies, threaten food security, and increase the risk of both overfishing and illegal, unreported, or unregulated (IUU) fishing activities.

Indeed, climate change already is progressively and negatively affecting tuna stocks and their associated fisheries. In this context, harvest strategies become increasingly urgent. Developing harvest strategies that account for climate change’s impacts on tuna biology, productivity, and population shifts will be paramount to balance trade-offs between catches of targeted species and their long-term sustainability.

Moreover, annually monitoring harvest strategies’ effectiveness to identify rare and unforeseen events—a process known as exceptional circumstances—could help to issue timely alerts and spur subsequent actions related to climate change. In this sense, decision-makers will need to focus on medium- and longer-term time horizons in order to adapt the governance to such events.

While scientists continue their work to better understand tuna population dynamics under climate change, RFMO adoption of harvest strategies as an adaptive management solution generally remains an antidote to the unpredictability fisheries face.

Some Progress on Harvest Strategies

Tuna RFMOs can look to harvest strategies as an important tool to begin addressing the impact of climate change on tuna population abundance and distribution. And the good news is that RFMOs have been making some progress in this area. For example, last year in the Eastern Pacific Ocean, the region’s RFMO adopted a harvest strategy for North Pacific albacore tuna, including a harvest control rule, as well as interim reference points for skipjack tuna. In December 2023, fisheries managers in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean implemented comprehensive harvest strategies for Western Pacific skipjack and Northern albacore. (A full review of RFMO progress on harvest strategies is available here.)

Similar, more widespread progress is now urgently needed across all of the world’s tuna stocks, and ISSF is continuing to press for the accelerated adoption and implementation of harvest strategies in all tuna fisheries. By rallying our partnerships from the diverse sectors of industry, science, and the NGO community to this common cause, we can issue a powerful and united appeal for progress on this critical aspect of fisheries management.

Dr. Hilario Murua is a Senior Scientist at the International Seafood Sustainability Foundation (ISSF). Visit the ISSF website at www.iss-foundation.org to learn more about tuna fisheries sustainability.

Author——————————-

David Gershman

Officer, International Fisheries

✉️

When the annual meeting of the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC) wrapped up December 8th after a marathon 19-hour final day of negotiations in Rarotonga, Cook Islands, members had made significant progress in the development of harvest strategies for skipjack and albacore tunas.

Fisheries for skipjack tuna from this region supply more than half of the skipjack for canning worldwide. In 2022, WCPFC adopted a management procedure (MP) for skipjack tuna, but it failed to ensure a clear link between the output of the MP and the controls on catch and effort on the water, which are managed by a separate conservation and management measure on tropical tunas.

This year, WCPFC adopted a provision in the tropical tuna measure that effectively implements the MP’s output. This language, proposed by the Pacific Islands Forum Fisheries Agency – which includes the Pacific Small Island Developing States and Australia and New Zealand – ensures that if the MP-based cap on total effort/catch for purse seine and pole and line fisheries are exceeded, the tropical tuna measure will be re-negotiated to keep fishing within the MP’s levels. This is a very positive step as the Commission works toward developing hard limits for all purse seine fleets fishing on the high seas and an allocation framework in the coming years. Development of the skipjack MP was led by the Pacific Island member States, and the adoption of this language demonstrates the commitment of those members to ensuring the success of the MP.

Albacore tuna stocks in the northern and southern hemispheres also got a boost. WCPFC adopted the operational piece (i.e., a formulaic harvest control rule) of a fully specified MP for north Pacific albacore, mirroring an agreement from August by the Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission which manages the stock in the eastern Pacific. This creates the first pan-Pacific and multi-RFMO MP. Although the WCPFC agreement was not drafted as a conservation and management measure (CMM) and is instead considered a binding harvest strategy, it sets clear expectations for management of the stock that should be bedded into a CMM when the Commission does more work next year to translate the MP-calculated fishing intensity into on-the-water controls.

To the south, the Commission revised a proposal by several south Pacific nations and Australia and adopted an updated interim target reference point (iTRP) for south Pacific albacore. The revised iTRP is defined as 4 percent less than the average level of spawning biomass experienced during the period of 2017-19, currently equivalent to 49% of unfished biomass, a level that is seen as precautionary. The stock is healthy, though declining, and the iTRP is necessary to advance the development of a full MP to bring greater stability and economic profitability to the fishery.

To that end, the Commission agreed to hold a scientist-manager dialogue meeting in 2024 with a focus on reviewing the performance of proposed harvest control rules for south Pacific albacore. That meeting will also discuss the development of target reference points for bigeye and yellowfin tunas, and review a monitoring plan for skipjack tuna. The first scientist-manager dialogue held in 2022 was successful in advancing development of the skipjack MP forward to adoption that year, and this agreement to hold a second dialogue meeting sets up 2024 as a year to make further progress on the development of harvest strategies.

With these decisions, WCPFC members have shown how they can work together to develop more modern approaches to managing these globally significant tuna fisheries, ending 2023 on a high note for harvest strategies. We look forward to even more progress next year.

Author——————————-

Claire van der Geest

Principal, Seven Seas Consulting

✉️

Harvest strategies improve fisheries management by setting the parameters and boundaries for stakeholder engagement in fisheries management from the outset. In the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC), harvest strategies are being actively progressed through Conservation and Management Measure 2014-06 to develop and implement a harvest strategy approach for key fisheries and stocks in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean (WCPO) and specifically through the workplan pursuant to paragraph 13 of the CMM last updated in December 2022. To date, the Commission has agreed the target reference point and management procedure for skipjack, with target reference points for south Pacific Albacore, Yellowfin and Bigeye tunas being ‘noted’. WCPFC will consider some proposals to continue the development of, or refine the existing, harvest strategies for key target species, including for example Northern albacore in coordination with the Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission adopted at its meeting in August.

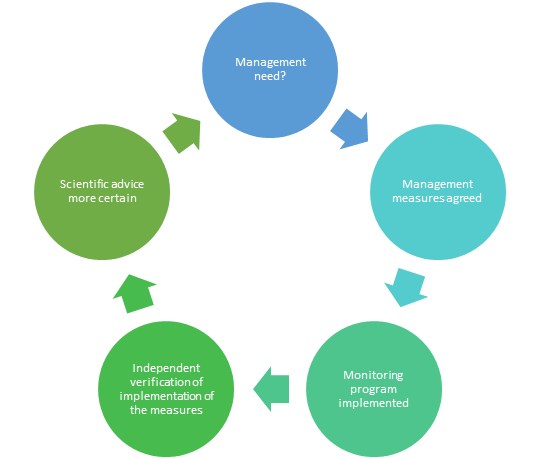

Fisheries management is not rocket science, but it is complex, relying on its two wings; (i) the management measures themselves in combination with (ii) a robust monitoring program to independently verify implementation of the measures on the water. Underpinning both wings and essential to harvest strategy development is to use the best available science to develop the management measures that will be used to achieve the target reference point. These management measures might consist of input or output controls or a combination of both depending on the fishery. Equally essential is to have an effective monitoring program to provide independent and verified data about activities on the water.

Although possibly not the sexy side of fisheries management, the importance of effective fisheries monitoring programs cannot be understated. Monitoring provides essential information for fisheries management such as at sea activities, catch, effort, and location of effort. The data generated from effective monitoring programs is used to strengthen the science underpinning the stock assessment and management procedures, which is used to further refine the management measures, helping to ensure that they rebuild or maintain the stock at the target reference point agreed in a harvest strategy. Effective monitoring, using both on-water and land-based tools, drives the continual improvement cycle that is fisheries management. Robust monitoring also helps to ensure that managers and stakeholders are confident that the approach to managing the stock is working, or if it’s not that effective action can be taken to quickly ameliorate any stock decline.

However, the adoption and implementation of monitoring programs and tools can be highly controversial and political. For example, the use of electronic monitoring to collect independent and verified data of activities at sea, including the placement of cameras in the workplace, has been met with significant resistance despite the inability to meet the existing agreement to achieve a minimum of 5% observer coverage to achieve the same objective. The resistance to the uptake of electronic monitoring comes from all stakeholders. For industry the implementation of cameras in their workplace is seen as an invasion of their privacy, unnecessary and costly. While for governments there is the need to balance the differing stakeholder perspectives (industry and conservation) to ensure confidence in the fisheries management while also delivering cost effective programs, including balancing the upfront costs with the ongoing costs of the program delivery. Concurrently, there are a need to understand how to utilise technology development to continue to drive down program costs and provide robust and rigorous fisheries management.

Fisheries managers would be wise to remain open to considering how technological advancements can be used in monitoring programs. For example, the use of Artificial Intelligence, with further development, may one day be an important addition to fisheries monitoring. All avenues to gather more precise and fine-scale fisheries data is essential to ongoing refinement of harvest strategies. Similarly, the smart use of analytics combined with bigger data affords the opportunity to garner previously unseen patterns important to further understanding the fishery. This will continue to be particularly critical as we try to manage fisheries in a changing climate.

Essential to harvest strategies is to consider not only the data required from the monitoring program and the tools to achieve it, but also how the monitoring tools and programs coalesce provide an integrated monitoring program (see WCPFC Skipjack example below). Considering how a management procedure along with the specific management measures will be monitored through tools like EM is fundamental to ensuring the success of the overall harvest strategy and is critical to consider throughout the harvest strategy negotiations. It is essential that fisheries monitoring be considered in a wholistic way to ensure that it effectively supports the broader fisheries management program implemented through harvest strategies.

Case Example: WCPFC Skipjack

Annex III of WCPFC’s Skipjack Management Procedure sets out at a high level of the type of information required for the management procedure, for example annual catch estimates and standardised CPUE indices, and CMM 2021-01 sets out the management measures are being used to ensure that the target reference point is achieved on average. However, neither the management procedure nor CMM 2022-01 describe the monitoring programs used to independently monitor the implementation of the management measures themselves. Rather the existing monitoring programs, for example the Regional Observer Program, the VMS and electronic reporting, have been developed generally rather than specifically to deliver harvest strategies or being seen as part of an integrated monitoring program. Thankfully the Secretariat has prepared a very useful summary linking the data collection and monitoring currently in place to support harvest strategies (WCPFC20-2023-14-Rev1).

Author——————————-

David Gershman

Officer, International Fisheries

✉️

The western and central Pacific is the world’s largest source of canned tuna. Skipjack tuna and albacore tuna are the two species predominantly caught for the canned tuna market and which are valued at $10 billion.

When the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC) meets Dec. 4-8 in Rarotonga, Cook Islands, the region’s fisheries managers will have a chance to ensure the long-term sustainability of these two vital species by making further progress in developing management procedures.

A management procedure (MP) is a pre-agreed strategy for making fisheries management decisions such as setting limits on catch or fishing effort. Also known as a harvest strategy, a management procedure helps ensure sustainability by allowing managers to select the harvest control rule that is predicted through computer simulation to perform the best at maintaining the stock and fishery at desirable levels.

Albacore tuna, managed as separate stocks north and south of the equator, features prominently on the agenda of the WCPFC. Last year, WCPFC adopted nearly all elements of an MP for the north Pacific albacore stock. This year, it has a chance to fill in a critical missing piece – the information needed to operationalize a formulaic harvest control rule.

Having already been adopted in the eastern Pacific by the Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission, adoption by WCPFC would create the first multi-regional fisheries management organization MP in the world.

One reason to develop an MP is it avoids protracted and ad-hoc negotiations on how to adjust catch or effort levels because those rules are agreed in advance. But to do that effectively, the MP should be binding on members, and its output should be directly linked to the on-the-water controls that govern vessel behavior.

At WCPFC, there’s more work to do on that front for both north Pacific albacore and skipjack. For instance, the north Pacific albacore MP is being proposed as a ‘harvest strategy’ agreement, which some members see as a decision that can be binding on the Commission. To remove any doubt or question as to its legal status, WCPFC should adopt the MP as a conservation and management measure (CMM). That would ensure members are bound to all the elements of the management procedure.

The skipjack tuna management procedure, on the other hand, was adopted last year as a CMM, but members agreed to apply it on a trial basis for six years, regrettably meaning they reserved the right to ignore its output during this time.

Now that the management procedure has been run for the first time, it should set catch or effort levels for 2024 through 2026. The result calls to set maximum fishing conditions at various baseline levels, depending on the gear, so members should have greater comfort with this approach. What this means is the WCPFC doesn’t have to make any changes to fishing on the water, since recent fishing has been less than the amount permitted by the MP. That’s good news, but not the end of the story.

Skipjack is managed through the WCPFC’s tropical tuna measure, which also regulates opportunities for bigeye and yellowfin tunas. This complex measure reflects a careful balance of members’ national interests. It has various components – some fleets have limits in the international waters, some do not. Limits in some zones are fully utilized; others are mainly aspirational. Aligning the measure to make its scheme of limits more seamlessly automate the output of the MP will take time but is a necessary task.

But, as members renegotiate the tropical tuna measure, political considerations can come into play and risk overriding the scientific advice coming from the MP. In updating the measure, members’ first objective should be to ensure a clear link to the skipjack MP and that the total catch or effort of skipjack anticipated to take place in the next three years across the Western and Central Pacific Ocean is not greater than what is recommended by the management procedure.

South of the equator, the south Pacific albacore tuna stock, though currently at healthy levels, has been subject to discussions on improving the economic viability of the fishery and preventing a significant decrease in biomass. The fishery is an important food source and economic resource to several South Pacific nations and the territories of American Samoa, New Caledonia and French Polynesia. Vessels from China and Taiwan also fish for this stock in significant numbers.

This year, a group of south Pacific island countries and Australia are proposing a revised target reference point (TRP) for the south Pacific albacore stock, which is necessary to set an overall objective for the fishery’s performance and set the stage for the eventual development of the full MP. It’s important for WCPFC to adopt a revised TRP to stay on track in developing the MP to ensure economic and biological sustainability into the future. The existing TRP, which is not currently used in management, is set at achieving a specific percentage of biomass depletion, but it is susceptible to change when new information alters the historic perception of the trajectory of the stock. The proposal on the table aligns the TRP with the level of biomass depletion experienced during a recent period (i.e., 2017-19) and thereby future proofs the TRP.

WCPFC faces important decisions on the road to modernizing its fisheries and bringing greater predictability and stability to the world’s most important source of canned tuna. Fortunately, members have shown in the past that they can work together to achieve consensus on challenging issues. If that trend continues, WCPFC will take an important step toward safeguarding some of its most important fisheries.

Author——————————-

Shana Miller

Project Director, International Fisheries Conservation – The Ocean Foundation

We had high hopes for harvest strategies at the 2023 meeting of the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT), which just met for 8 days in Cairo, Egypt. Yet, when the gavel dropped yesterday, there was very little progress to show. Both management procedures (MPs) scheduled for adoption according to ICCAT’s own workplan, namely for North Atlantic swordfish and West Atlantic skipjack, were delayed until next year. The incremental steps planned for other species similarly ended in disappointment. The brightest outcome related to harvest strategies was a commitment to consider a management strategy evaluation (MSE) for blue sharks, adding two stocks to ICCAT’s harvest strategy list.

ICCAT started its swordfish MSE several years ago, building on a decade of scientific work on reference points. In 2023 alone, ICCAT convened 3 meetings for dialogue among scientists, managers and other stakeholders about management objectives, candidate management procedures, and other aspects of the MSE. The scientists had 4 formal meetings to advance the technical side of the MSE, in addition to nearly weekly informal meetings. Two draft proposals to adopt a final MP, one from Canada and another from the USA and European Union, were submitted to the meeting. But a late update to some fishing data – dating back to 2021 – required some modifications to the MSE, and this led to slight changes in CMP performance results. Those final results were not available until the first day of the annual meeting. This rattled some governments, making them nervous about adoption, even though the updated results had been reviewed by multiple experts without any red flags. The resulting discussion concluded with a rollover of the existing measure and a plan to review the MSE results more thoroughly next year alongside previously scheduled testing related to impacts on CMP performance of climate change and juvenile mortality. The experience highlights the need to carefully consider data lags in MSEs given ICCAT (and other fisheries organizations) still struggle to receive timely and accurate data from member governments.

The story for western skipjack was similar. ICCAT scientists had endorsed the MSE as complete and ready for MP adoption at their annual meeting in September. Decisionmakers had agreed to near-final management objectives at a meeting earlier in the year after adopting conceptual objectives last year. Brazil, who led the MSE work and is responsible for more than 90% of the catch, was poised to champion an MP measure for adoption. But a proposal never came. Again, a slight question about whether the science was watertight – a question which was not backed by any specific concerns – resulted in the MSE being sent back to the scientists for another year of work. What exactly they’re supposed to accomplish beyond the robust work they’ve already completed is unclear.

With an MP adopted for Atlantic bluefin tuna last year in one of ICCAT’s biggest successes ever, this year’s task was to adopt an exceptional circumstances protocol (ECP) to govern how to proceed should unforeseen and untested scenarios occur in the fishery. Five rounds of review led to a strong proposal being tabled at the meeting. Yet, minutes prior to adoption, a revised version appeared that allows not only decreases in catch limits but also explicitly enables increases under some circumstances. Exceptional circumstances are typically viewed as emergency situations that might require deviation from the MP before the next management cycle to protect a stock. A limit that is “too low” does not constitute an emergency, especially when considering that the quota for bluefin tuna in the eastern Atlantic and Mediterranean Sea is at its highest level ever. So, while an ECP was adopted to finalize the MP as fully specified, it could put more pressure on the scientists’ recommended response should exceptional circumstances be identified in the future.

Another disappointment was a failure to take incremental steps on the multispecies tropical tunas MSE for bigeye, yellowfin and eastern skipjack tunas, all stocks in urgent need of improved management. A U.S. proposal to start developing management objectives for the stocks failed to pass, despite all of the substantive text being bracketed for later completion. Further, the funding requested by ICCAT scientists to engage much-needed external MSE experts in the relatively complicated multispecies framework was approved but only at a greatly reduced level.

The silver lining for blue sharks will result in ICCAT scientists advising on the feasibility of conducting MSEs for the North and South Atlantic stocks. Their guidance is requested by 2025, finally putting an end date on a general request that has been included in each measure for the stocks since 2016. This should be an easy question to answer, since preliminary MSE work is already underway for blue sharks at ICCAT thanks to funding from the FAO Common Oceans project.

It was a tough meeting for harvest strategies, especially considering where things stood just a few weeks ago and despite the fact that this year did see the third running of the northern albacore MP, demonstrating the value of MP adoption for the governance of international fisheries. The northern albacore catch limit was increased by 25% to its highest level ever since the stock continues to grow. That should serve as motivation to replicate this success for ICCAT’s other priority stocks, but regrettably that wasn’t the case this year. Instead, ICCAT rolled these tasks over to next year’s already busy schedule. We hope everyone will learn the necessary lessons to ensure things stay on track moving forward. We look forward to providing a better update after ICCAT’s 2024 meeting.