Climate change has substantial implications for global fisheries. In fact, scientists project that related losses in fish biomass production in the coming decades will occur in many regions, including countries such as the Federated States of Micronesia and Portugal, that rely substantially on aquatic foods for their domestic protein supply. Further, climate change is already causing changes to geographic species distributions and species life histories, including aspects such as growth and reproduction, for stocks around the world.

In the face of these and other severe impacts, fisheries managers can develop and implement climate adaptive fisheries management measures including harvest strategies (HS), which are also known as management procedures. These strategies shift management of a fish stock from short-term and reactive decision-making to longer-term objectives, such as growing a fish population’s size, to support sustainable and profitable fisheries. HS are underpinned by a scientific assessment process known as management strategy evaluation (MSE), which ensures that management objectives can be met under a variety of environmental conditions. HS are also designed to help fisheries adapt to changing conditions.

To learn more about the intersection of HS and climate change, we performed a rapid review of recent peer-reviewed literature and found that:

To date, the results of this review have been shared with several RFMOs, including the North Pacific Fisheries Commission, the South Pacific Regional Fisheries Management Organisation, and the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas, and we hope that more fisheries managers will consider the results of the science in thinking through the role that harvest strategies can play in navigating the impacts of climate change to fisheries.

Dr. Emily Klein and Dr. Ellen Ward are officers working on The Pew Charitable Trusts’ conservation support and conservation science teams.

Ellen Ward, Ph.D., works with Pew’s conservation support team, where she focuses on furthering climate adaptation and resilience solutions in the U.S. and internationally.

Prior to joining Pew, Ward worked for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) as an international affairs specialist focused on climate change, water resources, and deep seabed mining, including representing the agency at negotiations of the International Seabed Authority in Jamaica. She previously worked on habitat conservation issues for NOAA Fisheries in Alaska and on water resources management for the Government of Yukon, Canada.

Ward holds a bachelor’s degree in physics from Columbia University and a master’s and Ph.D. in earth system science from Stanford University.

Emily Klein, Ph.D., leads Pew’s work to design research projects that use innovative analytical and modeling tools to improve what we know about marine and freshwater systems, and the human connections to them. She also works to advance inclusion, diversity, and equity within Pew, across our grantees, and in the natural sciences.

Before joining Pew, Klein studied the complex connections between people and nature to support future sustainability with Boston University’s Frederick S. Pardee Center for the Study of the Longer-Range Future. While there, she managed a project in collaboration with the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management to apply ecosystem models to inform decisions about sand mining for beach renourishment in offshore waters of the New England and the mid-Atlantic regions. Prior to this work, Klein employed models and other tools to support marine management and decision-making, including for marine protected areas under climate change in the Antarctic, and to investigate interactions between management and fishing communities.

Klein holds a bachelor’s degree in ecology, behavior, and evolution from the University of California at San Diego, a master’s in environmental conservation and doctorate in natural resources and earth systems science from the University of New Hampshire.

Pacific bluefin tuna make headlines in the world’s most prominent media outlets. “Overfishing causes Pacific bluefin tuna numbers to drop 96%.” “Massive tuna nets $3.1 million at Japan auction.” “Quota for big Pacific bluefin tuna to rise 50% amid stock recovery.” Next month, there is an opportunity for Pacific bluefin to earn their best headline yet: “Agreement on management procedure locks in long-term sustainability.” And that’s exactly what we hope we’ll be posting on this blog in mid-July.

In response to the decimation of the species to just 2% of its unfished level, Pacific bluefin managers called for the development of a management procedure (MP) to be tested using management strategy evaluation (MSE). The first dialogue meeting of scientists, managers, and stakeholders took place in 2018 to provide input on management objectives and other MP elements. Fast forward 7 years, and we have a final MSE, with 16 candidate MPs in the running for selection by the IATTC-WCPFC Northern Committee Joint Working Group on Pacific Bluefin Tuna (JWG) when it meets in Toyama, Japan, July 9-12. To prepare for that meeting, the JWG will host a webinar next week to review the final results and offer a Q&A session.

The key remaining decisions include:

For the TRP, we support neither the most aggressive nor the most conservative fishing rate, instead preferring a middle option to balance long-term catch and conservation.

For the ThRP, we support a level that is an adequate distance from the LRP to ensure that it is not breached.

For the LRP, we again support one of the central options that balances the tradeoffs between fishing and stock status objectives. We oppose the candidate MPs that do not include an LRP because LRPs are an essential element of all MPs, ensuring that the stock does not drop to a dangerously low level.

We do not have a position on the West:East split, but note that because the two options did not show much difference in terms of their conservation performance, a compromise between the values tested could also be considered as a viable alternative. Most importantly, the split should not prevent agreement on an MP next month.

The completed MSE represents the best available science for Pacific bluefin and provides performance results for stock status, catch, and fishery stability across a range of uncertainties related to stock productivity, fishery efficiency, and catch underreporting. By agreeing to an MP, the JWG will put the valuable stock on a path toward long-term fishery sustainability and profitability, with catches projected to increase over time for almost all candidate MPs as the stock is allowed to fully recover.

This is great news for the fishing industry and the seafood supply chain, all the way to the consumer of this coveted sushi selection. Adopting an MSE-tested MP could also open the door to for industry to secure sustainable seafood certifications, such as through the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC), increasing the bottom line for industry. Fishers will benefit from the predictability and transparency of a pre-agreed approach for setting annual catch limits, a stark contrast to the current ad hoc approach of political negotiations for 50 tonnes of quota here or 500 tonnes of quota there.

The deliberations of the following month have been in the making for almost a decade. Check back here in mid-July for the outcomes of the JWG meeting, which will hopefully pave the way for formal MP adoption in the western Pacific (at WCPFC) and eastern Pacific (at IATTC) later this year.

As a physical oceanographer, I’ve dedicated a significant part of my career, including my work with the North Pacific Fisheries Commission (NPFC), to understanding the intricate dance between our oceans and the valuable fish stocks they support. My focus has been on the challenges and impacts of climate change on the North Pacific marine ecosystem, and specifically, on its precious resource, Pacific saury.

For decades, fisheries management has often centered on regulating fishing activities. It’s well understood that fishing effort is a primary driver of changes in fish populations, and indeed, fisheries scientists continually study how fishing impacts fish biomass. However, the very foundation of this system – the marine environment itself – is also being fundamentally altered by climate change. This new reality demands a multi-faceted perspective. While the ocean environment alone cannot explain all fluctuations in fish catches, understanding its influence is becoming increasingly critical. My study aims to explore a complementary dimension: if we assume relatively constant fishing effort, how do long-term environmental variations, particularly those driven by climate change, directly influence fish abundance? This approach helps isolate and better understand the ocean’s role and, subsequently, how to better manage fishery resources, including through the development of science-based management procedures (MPs), also known as harvest strategies.

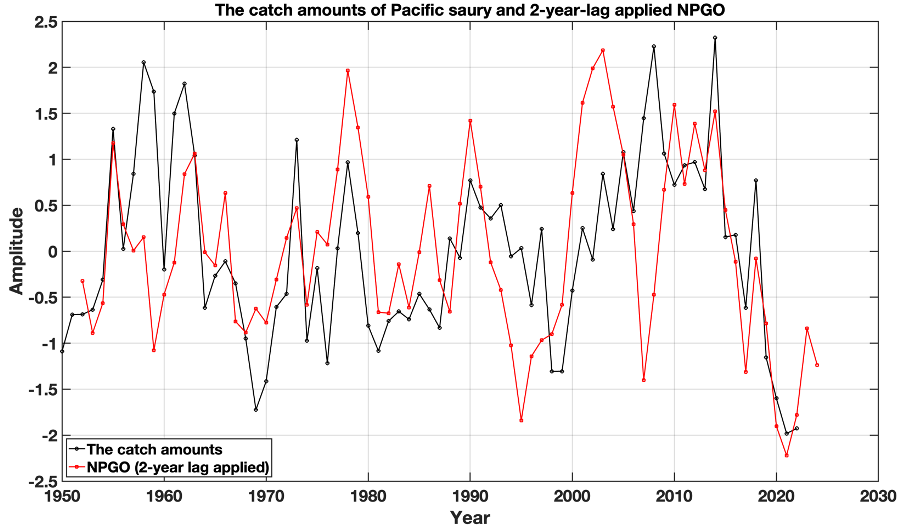

Pacific saury, once abundant at local markets and on dinner plates, has become scarce. This isn’t just an anecdote; data paints a stark picture. Figure 1 illustrates the plummeting catches of Pacific Saury in the North Pacific from 1950 to 2022, alongside the fluctuations of the North Pacific Gyre Oscillation (NPGO) Index, with a 2-year lag applied to the NPGO data. The recent decline in catch amounts (e.g., since 2010), coinciding with a similar phase shift in the NPGO index (from Positive to Negative), is a potent warning sign. This reflects the combined pressures of escalating climate change impacts and ongoing fishing activities, among other anthropogenic factors.

While large-scale climate phenomena like El Niño are well-known, the North Pacific has its crucial indicators, such as the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) and the North Pacific Gyre Oscillation (NPGO), which influence sea surface temperatures and marine ecosystems. By isolating the environmental component (under the assumption of stable fishing effort), my study revealed that the NPGO appears to wield a more decisive influence over the fluctuating fortunes of Pacific saury, as visually suggested in Figure 1.

How does an ocean-wide pattern like NPGO affect a specific species? These large-scale climate patterns influence major ocean currents, which serve as both highways and barriers for marine life. They also alter the distribution and abundance of phytoplankton and zooplankton – the primary food source for forage fish species like Pacific saury. Consequently, we’re seeing shifts in Pacific saury’s migration patterns. Recent increases in sea surface temperatures, a hallmark of climate change, are contributing to the shifting of Pacific saury fishing grounds further east as the fish seek suitable temperatures and feeding opportunities in a rapidly changing ocean. These NPGO-influenced shifts and broader warming trends can impact migratory routes, spawning times, and the suitability of traditional feeding grounds.

Perhaps the most striking discovery from my study is the predictive power inherent in the NPGO’s patterns when analyzed alongside Pacific saury catch data, under the assumption of relatively consistent fishing effort. As illustrated in Figure 1, a remarkably strong correlation emerged: specific shifts in the NPGO index can foreshadow changes in Pacific saury catches approximately two years in advance.

It’s an important question whether these observed shifts in saury linked to NPGO are solely due to its natural variability (e.g., ENSO, PDO, and NPGO) or if they are being exacerbated by broader climate change. While my study focused on the statistical relationship between NPGO phases and saury catch/distribution, it’s widely acknowledged that the North Pacific is experiencing significant warming, a trend primarily driven by climate change. This broader warming trend, particularly in traditional saury fishing grounds, undoubtedly interacts with natural climate patterns like the NPGO. Some scientific literature even suggests that climate change itself might influence the behavior and variability of these large-scale oscillations. Therefore, it is plausible that both the inherent cyclical nature of the NPGO and the overarching impacts of climate change are intertwined factors contributing to the observed changes in Pacific saury.

Regardless of the precise balance of these drivers, the two-year lead time offered by the NPGO-saury relationship provides a valuable, science-based tool. It allows us to anticipate potential future fluctuations driven by these environmental shifts. This foresight is critical and can be considered alongside dedicated analyses of fishing impacts conducted by fisheries scientists, offering a precious window of opportunity to implement and refine science-driven tools, such as MPs to best safeguard Pacific saury in a changing ocean.

The NPFC is tackling these combined challenges and spearheading efforts to integrate climate change considerations into MPs and stock assessments, while also continuing to manage fishing activities. This is where studies like mine contribute – by helping to untangle the environmental threads, we can transform abstract climate risks into manageable, actionable information. This scientific foundation empowers the NPFC to develop more sophisticated and robust MPs that are designed to be resilient to the uncertainties introduced by both climate change and other pressures.

A particularly powerful tool in this endeavor is Management Strategy Evaluation (MSE). MSE is a process where scientists and managers simulate the entire fisheries system under different conditions, including environmental and climate influences (like those identified in my NPGO study). The goal is to test how well different MPs can achieve pre-agreed objectives, helping to identify management approaches that are likely to perform best, even in the face of real-world uncertainties and changing conditions. My NPGO study, for instance, can provide valuable input for the “operating models” within MSE, helping to define plausible environmental scenarios – including those driven by climate change – against which these strategies are rigorously tested.

The NPFC has made commendable progress in advancing the management and scientific understanding of Pacific saury. Key milestones include finalizing the species’ first comprehensive stock assessment in 2024, which subsequently led to the establishment of a Total Allowable Catch (TAC). Building on this, an interim Harvest Control Rule (HCR) was adopted in 2024, based on preliminary simulation testing, providing a science-based framework for TAC determination. To further enhance long-term sustainability, the NPFC has proactively established a dedicated Small Working Group on Management Strategy Evaluation for Pacific Saury (SWG MSE PS). This group, which holds regular meetings and involves invited experts, is tasked with the critical work of developing a full MSE. As this group continues its work to develop a robust MSE, it is imperative that the NPFC ensures these evaluations explicitly consider and incorporate climate-related scenarios, including the effects of ocean warming, shifting migration patterns (like the eastward trend in saury catches), and other environmental impacts such as marine heatwaves, to build truly resilient management procedures for the future.

To comprehensively understand climate change impacts, NPFC is actively strengthening collaborations with international scientific organizations like the North Pacific Marine Science Organization (PICES). NPFC also supports initiatives like the Basin-scale Events and Coastal Impacts (BECI) project, which aims to create a North Pacific Ocean Knowledge Network. Additionally, NPFC can utilize its data-sharing agreements with other regional fishery management organizations to help identify areas for joint collaboration and share best practices regarding climate-informed management procedures.

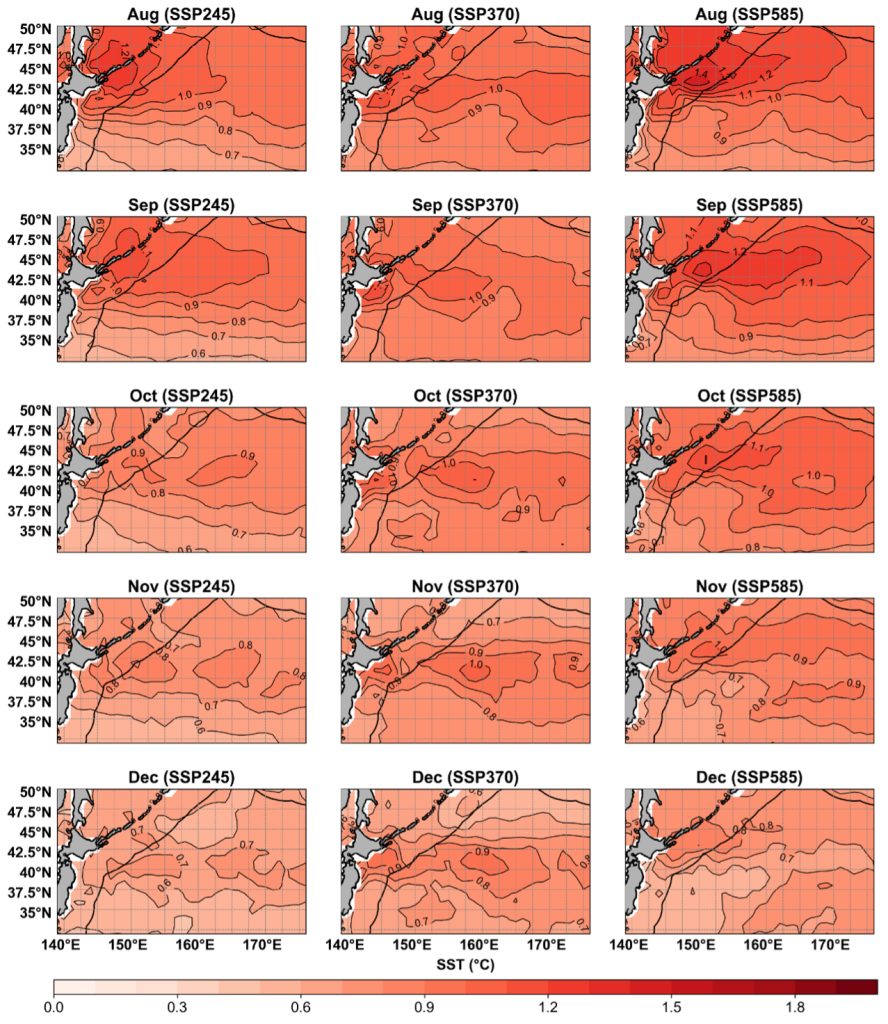

The goal is to build predictive models that can forecast future fishing grounds and stock productivity under various climate change scenarios. To illustrate the potential environmental shifts, Figure 2 displays projected changes in sea surface temperature (SST) across the North Pacific for the primary Pacific saury fishing season (August to December). These projections are based on different Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs), which are scenarios of future socioeconomic development used by climate scientists to model various levels of greenhouse gas emissions and resulting climate change.

As the maps in Figure 2 show, a consistent and concerning trend emerges across all SSP scenarios: a significant rise in sea surface temperatures is projected for the Northwestern Pacific during the peak saury fishing season. This warming is not trivial. For a species like Pacific saury, which is sensitive to water temperature, such sustained increases during their main feeding and migration period can have profound consequences. Warmer waters can alter their traditional migration patterns, potentially pushing them further eastward in search of cooler, more suitable habitats. This shift not only changes where fishing might occur but can also impact their survival rates and reduce their reproductive success by affecting spawning grounds and early life stage development. Therefore, understanding these projected SST changes across the entire fishing season under various climate scenarios is crucial for developing robust, forward-looking management strategies. While presenting multiple scenarios and months might seem like a lot of information at once, it is essential for appreciating the full spectrum of potential future conditions that NPFC’s management strategies must be prepared to address.

The journey through the North Pacific’s changing oceans reveals a stark reality: climate change presents a profound challenge, acting in concert with the ongoing impacts of fishing. Yet, there is a determined and collaborative response. My hope is that scientific endeavors, like my study on the NPGO’s influence (under specific assumptions to isolate environmental signals), provide essential building blocks for climate-adaptive MPs. These tools are about preparing for an uncertain future, ensuring management approaches are resilient and capable of safeguarding these valuable resources by considering all major drivers.

The path ahead is complex, but the commitment to science-based decision-making that considers all major drivers – both environmental and anthropogenic – offers a beacon of hope.

Dr. Jihwan Kim is an Oceanographic Engineer at Collecte Localisation Satellites (CLS) Group. He previously was a Fisheries and Data Scientist with the North Pacific Fisheries Commission.

We are pleased to announce that the www.HarvestStrategies.org host, The Ocean Foundation (TOF), has received a 2-year grant from the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) to facilitate the development and formal adoption of a management strategy evaluation (MSE) tested management procedure (MP) for South Atlantic albacore (Thunnus alalunga). The unique partnership commits funding from not just MSC, but also TOF and all five commercial fisheries with current or pending MSC sustainable seafood certification. Learn more in the official press release and explore the project page for updates and resources.

The project will support MSE development efforts led by the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT), which agreed to management objectives for the stock last year to serve as the guiding vision for a future MP. Funding will help independent MSE experts and ICCAT scientists to build the modelling framework to identify the MP options most likely to achieve the agreed objectives.

Katherine Collinson, Fisheries Certification Specialist for one of the industry partners, Tri Marine International, said, “By targeting long-term sustainability and resilience, this project will create a replicable model that enhances both compliance with MSC standards and sustainable management for the South Atlantic albacore fishery. This work will specifically advance the necessary progress of all MSC-certified South Atlantic albacore fisheries, which require the implementation of well-defined harvest control rules, like its northern stock counterpart.”

Jack Huang, Manager of Commercial, Operation & Compliance for another project partner, Tuna Alliance Inc., said, “We are honored to receive this funding, which will enable us to strengthen sustainable fisheries management and further uphold our commitment to responsible ocean stewardship. With this support, we can enhance traceability, implement advanced monitoring measures, and collaborate globally with our partners to address the impacts on marine environments, fishery resources, and habitats. As part of the seafood industry, we recognize that safeguarding our oceans is essential for the long-term sustainability of our industry and the well-being of future generations. We value this opportunity to contribute to ocean conservation and look forward to making a meaningful impact through this collaboration.”

Arthur Yeh, Executive Vice President at FCF Co., Ltd., a lead partner on the project, added, “We are extremely honored that the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) has provided us with this invaluable opportunity, granting support in our journey toward fishery sustainability. This funding is particularly crucial as it directly supports our efforts in the South Atlantic Albacore Longline Fishery, enabling us to enhance stock assessments, improve traceability, and develop a scientifically robust and reliable harvest strategy.”

We at www.HarvestStrategies.org look forward to contributing to this innovative partnership to expand the transparent, science-based, results-driven management that MPs afford to the valuable stock of South Atlantic albacore.

The 29th annual meeting of the Indian Ocean Tuna Commission came to a close last week, following the 9th session of its Technical Committee on Management Procedures, IOTC’s science-management dialogue group on management procedures (MPs). There were encouraging steps forward on MPs for several fish stocks: allocated catch limits were set for bigeye and skipjack tuna, and funding was secured to restart the yellowfin MSE and kick off work on a management strategy evaluation (MSE) for blue sharks later this year.

Dividing the Pie: Swordfish and Skipjack

Last year’s Commission meeting saw terrific progress with the adoption of management procedures (MPs), also called harvest strategies, for both skipjack and swordfish that would set Total Allowable Catch (TAC) limits for the stocks. Remarkably, this marked the first-ever swordfish MP adopted by a tuna Regional Fisheries Management Organization (RFMO) and set the first TAC for swordfish in the Indian Ocean. Once an MP has been adopted for a stock, a critical next step is agreeing on an allocation scheme to implement the MP-based TAC. While the MP defines the overall ‘size of the pie’ (e.g., TAC), it’s the allocation scheme that determines how that pie is divided among member governments. Without it, the MP lacks both accountability and structure to ensure effective management. Unfortunately, the IOTC did not discuss a swordfish allocation scheme at this year’s meeting, putting the MP on hold until one can be agreed.

A 2016 harvest control rule (HCR) has set skipjack tuna catch limits through 2026; in the absence of a fully specified MP and allocation scheme, skipjack catches have exceeded the HCR-based TAC by as much as 30% each year since adoption. The MP adopted in 2024 will be used to set the TAC for the 2027-2029 period, and not a moment too soon – at a recent meeting, the IOTC Scientific Committee highlighted that environmental conditions (e.g., sea surface productivity) in the Indian Ocean are forecasted to enter a less favorable period for skipjack tuna recruitment, making it all the more critical to ensure that catches remain within agreed limits. At this year’s meeting, the Commission adopted a measure introducing an interim allocation plan to constrain catches from 2026, as well as a guide for how the future MP-based TAC will be allocated. After a decade of catch overages, this is a momentous step forward. The temporary approach is intended to bridge the gap until the Technical Committee on Allocation Criteria (TCAC) finalizes the proposed allocation scheme for the 2027-2029 TAC. The 15th Meeting of the TCAC will take place in July 2025.

Bigeye tuna MP in action

Bigeye tuna is managed under an MP adopted by the IOTC in 2022. Operating on a 3-year management cycle, the catch limits previously set by the MP expire this year. At this year’s annual meeting, the Commission agreed to set a new bigeye TAC of 92,670 tons for 2026–2028, representing a 15% increase from the previous catch limit. This adjustment is in line with specifications of the adopted MP, which allows for a maximum 15% increase (or decrease) in TAC from the previous limit. The successful and timely adoption of this updated catch limit highlights the advantage of managing stocks via pre-agreed MPs that streamline decision-making and reduce the need for prolonged negotiations.

Importantly, the new measure includes country-specific catch limits for the 8 major harvesters. Unfortunately, this leaves many smaller harvesters allowed to maintain their catch and effort at recent levels. This combination of hard limits for the large harvesters and soft limits for the small harvesters raises concerns about over-shooting the agreed-upon TAC – a troubling possibility given the latest stock assessment, which concluded that bigeye tuna is overfished and likely undergoing overfishing.

Progress for shark management

At its 28th annual meeting in 2024, the IOTC Commission requested that the Scientific Committee (SC) initiate an MSE process towards the development of an MP for blue sharks. With this year’s meeting wrapped, funding is officially on the table to move the work forward in the coming year. This is the most progress to-date by an RFMO towards management of a shark species via a MP – a huge step in the right direction for shark sustainability! A blue shark stock assessment is scheduled for completion later this year, which is well-timed for informing the development of Operating Models (OMs) for a blue shark MSE and ensuring that the MSE is grounded in the best available science.

No movement on yellowfin tuna

Two proposals – submitted by the European Union and Pakistan with South Africa – were brought to the Commission this year, each proposing interim catch limits for yellowfin tuna in 2026 and urging continued progress toward adopting an MP for the stock. However, both proposals were withdrawn until next year, after uncertainties in the catch-per-unit-effort (CPUE) data – a commonly used index of relative abundance in fisheries management – have been reviewed. The TAC for yellowfin will therefore remain at its current level.

Development of an MP for yellowfin tuna began in 2013, including the definition of limit and target reference points, with the first phase of MSE work kicking off in 2016. However, progress was put on hold due to issues with the OMs, which were based on a failed stock assessment model. With many of those issues now resolved in the latest assessment, the MP process should be restarted, and funding to support this work was secured at this year’s meeting.

A yellowfin MP will enable the IOTC to manage the fishery in a way that supports long-term sustainability, economic viability, and stability; continuing progress towards managing yellowfin in the Indian Ocean via a robust MP is the most efficient path to long-term sustainability. While the Commission has not set a target adoption date for a yellowfin tuna MP, some initial progress towards this work has begun and reference OMs will be presented by the 16th meeting of the Working Party on Methods (WPM) in October 2025.

What’s Next:

Other meeting outcomes included general Commission support for incorporating climate change considerations in management frameworks to ensure a proactive approach to managing fisheries under climate-related risks. MSEs are an effective approach to advance these and other ecosystem-based fisheries management (EBFM) objectives, facilitating the development of MPs that are robust to and can explicitly account for the effects of climate change on target stocks.

Finally, adoption of an MP for albacore tuna was originally slated 2025. Although progress is behind schedule, the TCMP agreed last week that albacore is the next target IOTC stock for MP adoption. Operating models for an albacore MSE were agreed upon at the 9th Working Party on Temperate Tuna (WPTmT) Data preparatory meeting in February 2025, and candidate MPs were to the TCMP meeting. Continued work on candidate MPs and the conditioning of operating models will be presented at the upcoming WPTmT Assessment Meeting in July, with an aim to present final results to the TCMP and Commission for MP adoption in 2026. At that point, IOTC will have MPs in place for 4 of its 5 major target stocks, leading RFMOs in application of the MP approach.

Deep-sea fisheries (DSF) provide valuable seafood and economic benefits, but the unique characteristics of deep-sea ecosystems and the slow growth, late maturity, and low reproductive rates of many deep-sea species pose scientific and technical challenges in their management. The application of the precautionary approach in this context is not just beneficial; it is critical for ensuring the long-term viability of these fisheries and the surrounding marine environment. Well-designed harvest strategies, also known as management procedures that define clear objectives and adaptive measures to achieve them are an accepted application of the precautionary approach and offer a structured framework for sustainable deep-sea fisheries management.

A virtual workshop organized by the Common Oceans Deep-sea Fisheries Project, held on October 15, 2024, brought together 87 experts from regional fisheries management organizations (RFMOs), policymakers, academia, NGOs, and industry stakeholders to discuss the application of the precautionary approach (PA) to DSF in areas beyond national jurisdiction. Below, we provide some of the key discussion points, recommendations, and outcomes from the workshop.

Understanding the Precautionary Approach

The PA is a fundamental principle in sustainable fisheries management, emphasizing risk-averse management approaches to prevent overfishing and ecosystem damage. Accentuating preventive measures, this approach is particularly relevant for deep-sea fisheries, where data may be sparse, and the ecological impacts of fishing practices are not fully understood. The PA is underscored by international agreements such as the UN Fish Stocks Agreement (UNFSA), the FAO Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries (CCRF), and the International Guidelines for the Management of Deep-Sea Fisheries in the High Seas.

The virtual workshop focused concretely on applying the PA to DSF management with the objective of ensuring the long-term sustainability of stocks. Within this context, it explored the usefulness and feasibility of adopting long-term management plans for key target DSF stocks, which define clear objectives and establish threshold biomass points that trigger specific management decisions.

Workshop Highlights

The Workshop aimed to assess existing practices, identify challenges, and propose measures for strengthening the application of the PA to DSF. The discussions revolved around:

International Policy and Legal Frameworks

Scientific Considerations

Case Studies of PA implementation from dsRFMOs:

Integrating Harvest Strategies into DSF Management

Key Challenges

While the importance of PA in DSF management is well-recognized, several challenges hinder its effective implementation:

Recommendations for Strengthening PA implementation

Participants proposed several actionable steps to support the application of the PA:

1. Capacity Building & Training

2. Guidance & Best Practices

3. Strengthening RFMO Processes

4. Expanding Access to Tools & Resources

Conclusions and Looking Ahead

The DSF Project’s workshop underscored the importance of integrating the application of the precautionary approach to ensure the long-term sustainable management of deep-sea fisheries. The workshop emphasized the need to approach management with a long-term vision and highlighted the potential of harvest strategies to meet this need. The DSF Project and partner organizations remain committed to advancing good practices in DSF management, ensuring that deep-sea fisheries resources remain resilient and productive for future generations.

About the Project

The Deep-sea Fisheries under the Ecosystem Approach (DSF) project is one of five child projects of the Global Environmental Facility funded Common Oceans Program Phase II (2022-2027). The DSF project is implemented by FAO and executed by the General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean (GFCM) in collaboration with co-financing partners, which include the seven regional fisheries management organizations (RFMOs) responsible for the management of deep-sea fisheries stocks in areas beyond national jurisdiction (ABNJ)[1], as well as other international and national organizations[2]. The objective of the project is to ensure that DSF in the ABNJ are managed under an ecosystem approach that maintains demersal fish stocks at levels capable of maximizing their sustainable yields and minimizing impacts on biodiversity, with a focus on data-limited stocks, deepwater sharks, and vulnerable marine ecosystems.

Resources

To learn more about deep-sea fisheries, make use of our free E-learning course on Strengthening deep-sea fisheries management in areas beyond national jurisdiction

To take part in deep-sea fisheries technical discussions, join our Deep-Sea Fisheries Technical Forum

[1] General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean (GFCM), North East Atlantic Fisheries Commission (NEAFC), Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Organization (NAFO), North Pacific Fisheries Commission (NPFC), South East Atlantic Fisheries Organization (SEAFO), Southern Indian Ocean Fisheries Agreement (SIOFA) and South Pacific Regional Fisheries Management Organization (SPRFMO)

[2] International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES), Southern Indian Ocean Deepsea Fishers Association (SIODFA), International Coalition of Fisheries Association (ICFA), and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) of the United States of America

About the Authors

Eszter Hidas is the Project Manager of the Common Oceans Deep-Sea Fisheries Project (2022-2027). Eszter is a marine ecologist by training and has worked in the field of international fisheries policy and management for the last 17 years, with placements in Ho Chi Minh City, Barcelona, Brussels, and Rome. In addition to other organizations, she worked for WWF for 8 years before transferring to FAO, where she has been based for the last 6 years.

Sarah Fagnani is an international fisheries policy and legal expert currently working with the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) on Global Environment Facility (GEF) projects focused on deep-sea fisheries governance and the implementation of the BBNJ Agreement. With extensive experience in fisheries policy, legal frameworks, and international regulatory compliance, she has contributed to key initiatives aimed at strengthening fisheries management, combating illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing, and enhancing monitoring, control, and surveillance (MCS) measures.

At FAO, Sarah is actively engaged in policy gap analyses, stakeholder consultations, and capacity-building efforts to support sustainable fisheries governance at national, regional, and global levels. Her work includes facilitating intergovernmental cooperation, developing legal and technical guidance, and assisting countries in aligning their regulatory frameworks with international commitments.

With a strong background in policy development, legal advisory, and multilateral collaboration, Sarah is committed to advancing science-based, sustainable fisheries governance to ensure the long-term health of marine ecosystems.