As we continue our deep dive into Management Strategy Evaluation (MSE) with Dr. Tom Carruthers, CEO of Blue Matter Science, this second and final part focuses on the advanced perspectives and future directions that shape the evolution of MSE in fisheries management. From the integration of Ecosystem-Based Fisheries Management (EBFM) principles to the impact of climate change and technological advancements, this discussion delves into how MSE can address the complex challenges facing our ocean. With his extensive experience, Tom shares invaluable insights on stakeholder engagement, international collaboration, and the need for modern innovation.

HS.org: How do you perceive the integration of EBFM principles within current MSE frameworks, and what strides must be taken to ensure a holistic approach to fisheries management that adequately protects marine biodiversity and supports the resilience of oceanic ecosystems and the sustainability of fisheries?

Tom: Ah, EBFM. Scarcely has there been a topic in fisheries of so much discussion and so little management action! A few years ago, I was asked to review the history of EBFM in fisheries. Despite many hundreds, maybe thousands of papers on the subject spanning more than 15 years, I could find evidence of only one fishery, Atlantic menhaden, where the principles of EBFM had shaped tactical management advice.

In my view, MSE is the only existing framework that can operationalize EBFM in the routine provision of tactical advice. This is because most ecosystem models are difficult to evaluate empirically. They often struggle to pass conventional standards of peer review for models used to inform management advice. MSE is expressly designed to navigate such hypotheses, potentially ending in an adopted harvest strategy robust to hypothetical scenarios for ecosystem dynamics.

HS. org: How do you involve stakeholders, including fishers and conservation interests, in the MSE process, and why is their involvement crucial?

Tom: A common reason for pursuing MSE is that the conventional stock assessment approach excludes the interests, experience, and values of the wider group of fishery participants. To many participants whose livelihoods are directly impacted by the results of stock assessments, the process can feel like a technologically complex exercise that removes all but a handful of nerdy scientists and reviewers (I am probably one of those!).

Stock assessment is like designing a car engine – it is necessarily complicated. MSE, on the other hand, is more about driving the car – the controls and the instrumentation. MSE asks stakeholders what they know and care about and how best to achieve those outcomes. All this should be presented in a package that is easy to drive, with the focus being on where we are going, not the complexities under the hood.

HS.org: How have recent technological advances and data analytics improved the MSE process?

Tom: We’ve come a long way from coding a bespoke MSE from scratch for every case study. Packages like FLR and OpenMSE standardize data inputs and harvest strategy configuration, allowing for greater focus on the more important issues, such as management objectives and the harvest strategies themselves.

My colleague, Dr. Adrian Hordyk, has been working hard on Slick, which is a package and online app that presents MSE results and diagnostics using graphics conceptualized by scientific communications experts. All together, this new technology has made MSE much more accessible and efficient.

HS. org: Where is there even more room for improvement?

Tom: MSE is still relatively new in the field of fisheries science and management. As a result, MSE processes tend to be rather ad-hoc and differ among fisheries management organizations and stocks. Much could be learned and synthesized from these various applications.

Having the tech to do MSE easily is one thing. What is needed now is an established framework, an MSE roadmap of sorts, that is integrated with stakeholders and the tech so that the process is standardized, efficient, and disciplined. As it happens, this is something we are currently working on; what are the odds?!

HS.org: How does MSE help adapt fisheries management to the impacts of climate change?

Tom: In a way, this is similar to the question about MSE and EBFM above.

Just about every fishery management organization I know of has an objective along the lines of ‘implement management considerate of changing climatic conditions.’ Despite a huge amount of scientific literature naming possible impacts, there are very few that make quantitative predictions that could be used to inform management advice. From my perspective, the forecasting of climate impacts on fish populations is necessarily hypothetical. I simply don’t think we can reasonably evaluate the credibility of an ‘end to end’ model that combines the predictions of climate, oceanographic, ecosystem, physiology, and fleet models to forecast impacts on a fishery. This is a problem for the conventional stock assessment approach that focuses on scientific veracity. This is less of a problem for MSE, which focuses on harvest strategy robustness, including robustness to highly uncertain future fishery scenarios. MSE might be the only framework we have available for establishing tactical advice for fisheries, providing us with harvest strategies that have demonstrated climate readiness.

HS.org: What roles do climate change and environmental variability play in shaping MSE approaches?

Tom: In general, these phenomena interact with the types of harvest strategies being tested. In an attempt to consider possible climate change or environmental conditions, MSEs often simulate changes in future stock productivity. Systematic productivity shifts tend to favor harvest strategies aiming to fish a consistent fraction of the stock over those that aim for a particular stock level. Variable stock productivity tends to favor harvest strategies that are responsive to recent data and allow for larger changes in management advice. Depending on resource conservation objectives, climate change, and other challenging environmental scenarios can be highly influential in harvest strategy selection if they provide an extreme stress test.

HS.org: What role does international collaboration play in developing and applying MSE, especially for transboundary fisheries?

Tom: Collaboration on both scientific and management aspects is absolutely essential. On the science side, an MSE for an international transboundary stock almost always requires the timely submission of standardized data from all fishing nations and a shared understanding of the important fishery uncertainties. Although these may already be a part of an existing stock assessment process, MSE tends to go further and allow for a wider range of data and hypotheses.

You could argue that the most important collaboration occurs at the management level, where I have less experience. Those managers must agree on aspects that may include the mundane, such as how often to update advice; the important, such as the principle management objectives; and the contentious, such as catch allocations. For transboundary stocks, international collaboration can be seen as an opportunity and a strength, but it is also a necessary precondition of MSE.

HS.org: In your opinion, which regional fisheries management organizations (RFMOs) are leading the way in adopting and refining MSE practices? What lessons can be learned from these pioneers that could be applied globally?

Tom: I think CCSBT does a remarkable job of including new genetic technology in their MSE frameworks, not just in defining fishery hypotheses but also in the harvest strategy itself. I think the lesson from CCSBT is to keep innovating and looking for new sources of scientific information.

Now, sadly, I am biased toward those processes I have had some direct involvement with:

The Canadian DFO is leading the way with data-poor and data-moderate MSE frameworks in B.C. DFO has established a framework for its groundfish fisheries that allows for the rapid adoption of simple empirical harvest strategies where a stock assessment is not feasible. The lesson from DFO is that MSE is not necessarily an exercise for data-rich stocks – the whole idea of establishing tactical advice in the face of uncertainty is very much a data-poor fishery problem.

HS.org: What do you see as the future directions for MSE in fisheries management over the next decade?

Tom: In the next decade, MSE should:

HS.org: What are the key research questions or areas that, if addressed, could significantly advance the field of MSE? Are there particular gaps in our current understanding or methodology that need to be filled?

Tom: For the most part, we still think of fishery management in terms of individual species and data streams for individual species. From the early work I have been doing, it is apparent that if we consider multiple stocks together, the data may have considerably more information about stock and exploitation levels. I think there must be more investigation into multi-species MSEs and harvest strategies. We could be ignoring a lot of information.

In most cases, MSE has been used to establish a harvest strategy that sets a catch limit. There needs to be a greater focus on the efficacy of mixed management options, such as a catch limit in combination with other regulations such as bag limits, effort limits, spatiotemporal closures, and size limits. Exploration of mixed management controls often reveals opportunities to obtain a superior trade-off in yield and resource conservation.

HS.org: What advice would you give fisheries managers and scientists who are new to MSE and looking to implement it in their region’s fisheries?

Tom:

Dr. Tom Carruthers’ insights highlight the critical role of innovation, collaboration, and a disciplined approach in advancing MSE to address the evolving challenges in modern fisheries management. By focusing on efficiency, stakeholder engagement, and adapting to environmental changes, MSE can provide robust and sustainable solutions for the future of our oceans. To learn more about MSE and Tom’s work, please visit www.bluematterscience.com.

Blue Matter Science, led by CEO Dr. Tom Carruthers, is a leading organization dedicated to advancing marine science and sustainable fisheries management. With a background in marine biology, experimental ecology, and a PhD in applied mathematics from Imperial College, Tom is also an Adjunct Professor of Fisheries Science at the University of British Columbia. His passion for problem-solving in marine science drives his current focus on developing tools that support robust fisheries management.

In this two-part blog series, we delve into the nuanced landscape of MSE with Tom, unpacking the fundamental components that render MSE indispensable in our collective pursuit of ecologically responsible and economically viable fisheries management.

HS.org: In 50 words or less, can you explain what Management Strategy Evaluation (MSE) is and why it is an important tool in international fisheries management?

Tom: International fishery managers are tasked with implementing a harvest strategy that meets the objectives of diverse stakeholders, often in the face of large scientific uncertainties. MSE is a computer simulation approach that tests candidate harvest strategies across various scenarios for the fishery to identify those that can robustly achieve management objectives.

A common analogy for MSE is the testing of pilots using a flight simulator. In the MSE context, harvest strategies are the pilots being tested. Instead of flying conditions, MSE simulates a plausible range of biological, ecological, and exploitation scenarios for the fishery. Like a flight simulator, MSE can provide us with confidence that a harvest strategy (the pilot) will perform well over a wide range of conditions.

HS.org: What are the key components of an effective MSE process, and how do they interact to ensure the long-term sustainability of fisheries?

Tom: MSEs are pursued for various reasons, so ‘effective’ is somewhat case-specific. In the case of Atlantic bluefin tuna, there were difficulties in establishing a scientifically defensible assessment of the resource for use in decision-making. Essentially, there were many hypotheses for biology, ecology, and behavior that were similar to the data. For Bluefin, MSE was all about establishing a simple harvest strategy that was demonstrated to work robustly across all those hypotheses. The challenge in the South African sardine and anchovy fishery was establishing a harvest strategy that could allow for fishing without serious overexploitation of either species. In the case of the Bay of Fundy herring, MSE was used as a sort of ‘due diligence’ for a harvest strategy that had already been adopted and was in use. This might sound like a rather pedantic start of an answer to your question, but it goes to a point: arguably, the most important part of an MSE process is identifying a clear problem statement. Why MSE in this context?

There are three main parts to an MSE that interact in the adoption of a sustainable, robust harvest strategy:

Performance indicators are the basis for the scoring and comparison of harvest strategies. They are the lens through which all participants will view results. The performance aims of managers will be revealed when a harvest strategy is adopted. An effective MSE is one built around participation and communication. It should include a comprehensive consultation process with a range of stakeholders to ensure that their perspectives and values are communicated in results. Any legal requirements for fishery managers should also be expressed as performance indicators. Once established, the set of performance indicators provides a transparent account of harvest strategy strengths and weaknesses. It allows managers to explicitly consider trade-offs between, for example, extraction and conservation objectives. If the performance indicators part is done right, when a harvest strategy is adopted, it is clear why it was selected.

An effective MSE is one where managers have confidence in the adopted harvest strategy. That confidence arises from testing candidate harvest strategies against a wide range of plausible uncertainties (hypotheses) in current and future fishery conditions. Although science is usually the primary basis for developing these hypotheses, an effective MSE process includes stakeholder knowledge and experience, allowing a range of perspectives on the fishery to inform the selection of an appropriate harvest strategy.

Now that we have established how to score them and the conditions by which they will be tested, it is vital to focus on the harvest strategies – the pilots in the flight simulator analogy. An effective MSE is an open process that allows for testing a diverse range of harvest strategies developed by multiple development teams. These teams engage in a collaborative competition where harvest strategies are compared and refined. This diversity, friendly competition, and ingenuity process extracts every possible ounce of performance from a harvest strategy. Within the constraints specified by managers, anything goes. For me, it’s the most fun part of MSE!

If I’ve answered this correctly, it should be clear why MSE is such a powerful tool in establishing a long-term sustainable harvest strategy for a fishery. MSE is 1) inclusive, open, and transparent. 2) accounts for economic and biological definitions of sustainability in performance indicators, and 3) selects a harvest strategy that has been shown to provide sustainability across a range of hypotheses for the system.

HS.Org: Despite the proven benefits of harvest strategies and MSE, widespread adoption has been slow in some areas. What are the primary barriers to the broader adoption of these management approaches, and how can they be addressed?

Tom: Technical overhead. Previously, a serious impediment to MSE adoption was developing all the code to do the simulation work. Today, MSE packages like FLR and OpenMSE take much of this burden away from the process, allowing it to refocus on performance indicators, uncertainties, and harvest strategy design – the things that matter. However, the false perception of MSE as an expensive, burdensome, complicated techno-rats-nest persists. A big part of our collaboration with www.harveststrategies.org and The Ocean Foundation has been about showing people that this is no longer the case. We have been to management settings with OpenMSE, where managers and stakeholders were very organized, and harvest strategies were adopted in less than six months. A lot of managers and scientists don’t realize what is now possible.

Getting stuck in ‘Assessment mode’. The conventional approach to fisheries management is to develop a ‘best’ model of the fishery that is empirically validated by fitting to data and then used in management decision-making. Yes, you can look at alternative models and assumptions via so-called sensitivity analyses, but fundamentally the focus of stock assessment modelling is scientific veracity. That is not the focus of MSE, which is all about harvest strategy robustness. ‘Assessment mode’ is a condition that is a serious threat to the health of any MSE process. Scientists can get bogged down in the details of the models and data, which may affect perceptions of the stock but are often inconsequential to harvest strategy performance. Managers want to see stock assessments in their harvest strategies instead of simpler approaches that perform similarly. MSE projections are viewed as forecasts, not scenarios, for testing harvest strategies and so on. As is the case for many MSE problems, the solution is to do a thorough introduction to MSE and then get a demo MSE framework up and running as soon as possible so that all participants can see it in action and hopefully interact with it.

Indecision. MSE necessarily requires many decisions to be made, including who to include, when to hold meetings, when to draw a line on developing hypotheses, what performance indicators, what diagnostics, and what types of harvest strategies.

The list is enormous. This can drag out an MSE into an arduous process where momentum is lost to a point where new data and hypotheses emerge, and the process is stalled in a constant update loop. The best way to solve this is to employ an experienced chair of the process who can develop an MSE roadmap and maintain discipline on timelines.

HS.Org: How do you balance short-term economic interests with long-term fishery goals in MSE?

Tom: For most MSEs, the principal performance trade-off among harvest strategies is between what you take and what is left over in the water. Managers must navigate this trade-off between catches in the short term and biomass/catch outcomes over the longer term based on their established objectives and legal requirements. As a mere analyst, this is above my pay grade! Things are not as clear-cut as you might expect, however. I’m currently working on a harvest strategy for an invasive species.

Stay tuned for Part 2: Advanced Perspectives and Future Directions in Management Strategy Evaluation (MSE), where we dive deeper into the challenges, technological advances, and future directions of Management Strategy Evaluation in international fisheries management. Don’t miss the opportunity to learn more about how these modern approaches are shaping the sustainable future of our global ocean.

With the global demand for seafood increasing, the need to prioritize sustainable and responsible fisheries management has become increasingly urgent. An essential tool in achieving this goal is the development and implementation of a Harvest Strategy, which provides a comprehensive approach to guide decision-making in fisheries management. In Indonesia, a vast archipelagic country with abundant marine resources, robust Harvest Strategies are crucial to protect marine ecosystems and ensure the long-term viability of its fisheries. Indonesia has made significant progress in preserving its marine resources and launched a Harvest Strategy for Tropical Tuna in Indonesian Archipelagic Waters. The strategy aims to strike a balance between ecological conservation and the prosperity of Indonesian people. It is MDPI’s hope that the careful management of tuna resources will not only ensure their long-term availability but also create economic opportunities for coastal communities.

The importance for Indonesian small-scale fishers

Indonesia’s small-scale fishers play a crucial role in the country’s fisheries sector. Small fishing vessels (under 10 gross tons) represent nearly 90% of Indonesia’s fishing fleet and are responsible for more than half of the total catch, thus constituting the backbone of captured fisheries in the country. However, their vulnerability to changes in tuna populations necessitates careful management strategies to protect their livelihoods.

The Harvest Strategy for Tropical Tuna holds particular significance for Indonesian small-scale fishers. By encouraging sustainable tuna harvesting practices, the strategy could help secure their livelihoods while preserving the resource for future generations. The inclusion of small-scale fishers’ data strengthens the knowledge base, enhances their representation, fosters accountability, and promotes a sense of ownership among fishers and coastal communities. This collaborative effort highlights the importance of including diverse stakeholders and recognizing the significance of data from small-scale fishers in developing comprehensive and effective fisheries management strategies.

Since 2014, MDPI, along with small-scale fishers, have actively contributed to the development of the Harvest Strategy, providing valuable insights, technical assistance, and data collection efforts for the small-scale handline segment. This has helped address the specific complex dynamics of Indonesia’s small-scale fisheries. The integration of small-scale tuna fishers’ data into this Harvest Strategy has been a significant achievement, considering the limited data available for certain sectors of tuna fisheries, as well as the requirements, standards and technical challenges.

MDPI’s contributions to the Harvest Strategy extend beyond data provision to include scientific research, technical workshops, and capacity building efforts. MDPI’s early involvement as a data provider who had previously developed protocols to meet the requirements of Regional Fisheries Management Organizations, served as a catalyst for other governmental and non-governmental organizations to design data protocols that could contribute to the Harvest Strategy. MDPI’s expertise and commitment to sustainable fishing practices have facilitated evidence-based decision-making and fostered collaboration among stakeholders. “MDPI and other NGOs can contribute by filling the gaps that the government cannot fill,” said Toni Ruchimat, ex-head of the Marine and Fisheries Research Center, BRIN.

In May 2023, Dr. Fayakun Satria, Head of the Marine and Fisheries Research Center, BRIN, highlighted that “Without data from stakeholders, there is no Harvest Strategy. The Harvest Strategy will not succeed without collaboration.”

Wildan, Small-Scale Fisheries Lead for USAID Ber-IKAN, who worked at MDPI from 2013 to 2023, acknowledged the improvements made in tuna fisheries data through collaborations between various stakeholders, including the government, NGOs, and fisheries associations. He emphasized the importance of regularly discussing the Harvest Strategy and involving all parties, including businesses and fishers, to ensure shared understanding and active participation. In an interview with Mongabay in 2022, Wildan stated, “Through regular discussions on the Harvest Strategy, we hope that all stakeholders will be gradually engaged, including businesses and fishers. Given the highly scientific nature of this Harvest Strategy, it is not an easy task. It requires collective understanding and considerable energy and time to achieve our goals.”

Benefits, challenges, and future perspectives

Implementing the Harvest Strategy for Tropical Tuna brings numerous benefits. It can help maintain fish populations at sustainable levels, which could help ensure a consistent supply of seafood, thus enhancing long-term food security and safeguarding the income and livelihoods of those dependent on the sector. Through the implementation of responsible fishing practices, a sustainable Harvest Strategy can also help protect non-target species, reduce bycatch, and minimize the impact of fishing on sensitive habitats, supporting the overall health of marine ecosystems and promoting biodiversity conservation.

To achieve these objectives, several key management priorities have been identified: restrictions on the use of fish aggregating devices (FADs), area closures to protect spawning grounds, and establishment of Total Allowable Catch limits.

With the Harvest Strategy for Tropical Tuna, Indonesia has a goal to maintain the tropical tuna stocks above 20% of the unfished level with a 90% probability, known as the limit reference point (LRP). The goal is to prevent overexploitation and ensure long-term sustainable catches. The target is based on stock assessments conducted in different regions within the Western and Central Pacific Oceans.

However, developing and implementing a Harvest Strategy is not without challenges. Data limitations, stakeholder engagement, and enforcement of regulations are among the obstacles faced. Robust data collection and monitoring systems remain essential for accurate stock assessments and effective decision-making. Engaging stakeholders, including fishing communities, in the implementation process is necessary to foster a sense of ownership and cooperation.

MDPI has been supporting the dissemination of information and socialization of the Harvest Strategy by the Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries through the Fisheries Co-Management Committees, platforms that address current fisheries-related issues and engage various stakeholders, including small-scale fishers. Besides, strong enforcement measures and effective compliance mechanisms are necessary to ensure adherence to regulations and prevent illegal fishing practices. Additionally, flexibility and continuous evaluation are required to adapt the Harvest Strategy to changing environmental conditions, such as climate change impacts and shifting fish distributions. As Indonesia continues to prioritize sustainability and address the challenges associated with fisheries management, including by implementing this newly published Harvest Strategy, it can set an example for other nations in the pursuit of responsible fishing practices. Looking ahead, ongoing efforts are necessary to effectively manage tuna resources while ensuring that the voices of small-scale fishers are heard and the needs of coastal communities are addressed.

About the Author: Juliette Ezdra (she/her) was a Development Lead from 2021 to 2023 at Masyarakat dan Perikanan Indonesia (MDPI), a non-profit organization aspires to empower coastal communities in achieving sustainability by supporting community organization and harnessing market forces. Visit www.mdpi.or.id to learn more about tropical tuna harvest strategy in Indonesia.

References

Notohamijoyo A., et al. 2020. “Sustainable fisheries subsidies for small scale fisheries in Indonesia”. ICESSD 2019.

Have you ever wondered what a Harvest Strategy is? The concept might seem unfamiliar to many, but imagine playing a board game with your friends and family. The game you are about to play has evolved over time, incorporating innovative changes, updates, and additional features. Before starting, you gather around the kitchen table to read the instructions carefully. The updated game offers different pathways or strategies to win, but you must agree on the rules and choose one pathway for the entire game.

Now, let’s shift our focus to the world of fish, specifically tuna. Visualize hundreds of tuna swimming in our oceans, forming a single stock. These tunas, like any other living organism, undergo a life cycle from birth, growth, breeding, and eventually death. While they have their own growth and survival strategies, they face numerous threats, such as predation, disease, competition, and old age. These threats contribute to what is known as “natural mortality”, in other words: fish dying because of natural events. However, this is not the only concern.

Considering that the global annual consumption of aquatic foods reached approximately 20.2 kg per capita in 20201, aquatic foods serve as a significant protein source ensuring food security for humanity. To meet these resource requirements, thinking about how we fish becomes imperative. Fishing, an ancient human activity that has existed for thousands of years, employs different methods and gears depending on the targeted species. In addition to natural mortality, experts must consider “fishing mortality”, as fish stocks are prone to fishing, posing the greatest threat to commercial and other related fish species caught accidentally.

It can be argued that certain fishing methods have different ecological impacts, with some being more sustainable than others. When we examine a fishery closely, we realize it is far from a trivial activity. Ecological impacts are just one aspect to consider; socioeconomic factors also play vital roles. The fishing industry employs approximately 33 million people worldwide, from processing to preparing or selling, with an estimated economic value of landings of USD 20 billion. Tuna alone accounts for approximately 7% of this total1.

Returning to the game analogy, instead of playing with friends and family, imagine that the players are fishers and other stakeholders of a tropical tuna fishery. They all are competitive and want to win, and they each have their own goals and expectations, creating a complex dynamic. Fishers may aim to catch as much fish as possible in the shortest time, while NGOs may advocate for sustainable fishing practices and train communities, and scientists may have a more objective stance as they inform decision-makers based on data analysis. However, all players are interconnected, and the game becomes more complex when data consistently shows declining tuna trends, potentially leading to a scenario where there are no more tuna to harvest.

An example of a tuna species facing challenges is the yellowfin tuna (Thunnus albacares) in the Indian Ocean, which has been classified as overfished and subject to overfishing since 20182. Overfishing refers to depleting the stock of fish below the level that can sustain maximum yield.

To avoid this worst-case scenario and achieve harmonious and beneficial outcomes for all players, fisheries management becomes crucial. This is where a Harvest Strategy, also known as Management Procedure or Management Strategy, comes into play. Harvest Strategies are used by countries worldwide, including Indonesia, which launched its own Harvest Strategy for Tropical Tuna in Indonesian Archipelagic Waters in June 2023 with MDPI’s active support.

The launch of the Harvest Strategy for Tropical Tuna in Indonesia marks a significant milestone in the nation’s commitment to sustainable fisheries management. The involvement of diverse stakeholders, including MDPI, has played a crucial role in supporting data-driven decision-making and stakeholder engagement. The Harvest Strategy provides a roadmap for responsible fishing practices, balancing ecological, economic, and social objectives. Continued efforts and awareness raising are essential to effectively manage tuna resources, protect marine ecosystems, and support the future of Indonesia’s tuna fisheries and coastal communities.

A Harvest Strategy is a pre-agreed framework based on scientific advice and the best available data. By utilizing data and information about the fishery, experts can simulate different long-term scenarios, taking into account uncertainty and using computer models, to predict how stocks might behave3. This strategy is similar to choosing a pathway before starting the game. Experts can test and compare different scenarios based on fisheries science against agreed-upon management objectives, aiming to prevent stock collapse. This is known as a Management Strategy Evaluation, and is a key component of a Harvest Strategy3. If the available data for a Harvest Strategy is accurate and reliable, it could reduce the need for costly operations like stock assessments.

A Harvest Strategy follows a closed-loop process with different phases and a set of actions prior to its establishment. This includes monitoring and assessing the fishery, adjusting fishing levels based on harvest control rules4 (actions that describe how management measures should be adjusted in response to indicators of stock status), employing specific management measures, and enforcing and monitoring those rules to ensure that stakeholders are compliant. Collaboration among stakeholders is key to successful fisheries management, just like the cooperation among players in a game. Fishers, governments, NGOs, researchers, and other stakeholders must work together as a team to achieve sustainable outcomes. They can all contribute by collecting and sharing data, monitoring the fishery, sharing their expertise, and ensuring compliance with rules.

In conclusion, the Harvest Strategy is a game-changer for sustainable fisheries management. By incorporating scientific advice, data-driven decision-making, and collaboration among stakeholders, we can navigate the complexities of fisheries management and safeguard fish stocks for future generations. Just like in a board game, strategic planning and cooperation are essential for success!

About the Author: Kai Garcia Neefjes (he/him/his) is a Program Associate Specialist at Masyarakat dan Perikanan Indonesia (MDPI), a non-profit organization aspires to empower coastal communities in achieving sustainability by supporting community organization and harnessing market forces. You can contact him at kai.garcia@mdpi.or.id or visit www.mdpi.or.id to learn more about tropical tuna harvest strategy in Indonesia.

References

[1] FAO, The state of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2022. Towards Blue Transformation. (Rome: FAO, 2022), 51-82,

www.fao.org/3/cc0461en/cc0461en.pdf

[2] Indian Ocean Tuna Commission, 17th Working Party on Tropical Tunas Report. (IOTC, 2015),

www.fao.org/3/bf342e/bf342e.pdf

[3] CSIRO, Key concepts for Harvest Strategies and Management Strategy Evaluation. (CSIRO, n.d.).

[4] “Report of the 2018 joint Tuna RFMO Management Strategy Evaluation working group meeting,” June 13-15, 2018, www.tuna-org.org/Documents/tRFMO_MSE_2018_TEXT_final.pdf

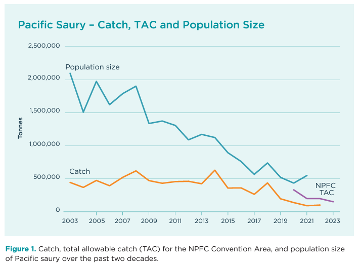

Pacific saury is one of the popular fishes in Korea. The general public enjoys it for its rich nutrition and affordability. People savour saury in various forms, such as grilled, canned, and semi-dried with diverse recipes. For example, canned saury in kimchi stew is a common lunch choice for business workers in Korea. Beloved by many Koreans and people around the world, saury is a keystone species for a healthy marine ecosystem and plays a crucial role as a climate change indicator species. However, Pacific Saury is facing a serious depletion crisis (see Figure 1).

Rising sea temperatures due to climate change seriously threaten saury and can alter its distribution and migration patterns during its peak fishing season from October to November. Climate change has already led to decreased saury harvests in the waters surrounding Korea and the broader North Pacific, which is further exacerbated by excessive fishing activities. With its short lifespan and sensitivity to environmental changes, saury presents challenges in predictable management. Given growing effects from climate change and threats from overfishing, a management procedure is urgently needed to protect saury for the long-term.

Harvest strategy discussions have begun within the North Pacific Fisheries Commission (NPFC), most notably with the recent adoption of a harvest control rule (HCR) for saury. HCRs are the operational component of a harvest strategy, which are essentially pre-agreed guidelines that determine how much fishing can occur based on indicators of the target stock’s status. Therefore, adopting HCRs is essential for recovering declining saury populations and effectively managing unpredictable changes. Some RFMOs have successfully implemented similar management procedures (MPs), including HCRs, for tuna and other species.

At the 2024 Commission meeting, the NPFC adopted an HCR for Pacific saury, which constrains the limits of the maximum change in catch (MAC) to 10% but sets an immediate total allowable catch (TAC) of 135,000 metric tons. Some member states supported an HCR with a MAC of 40%, but others favoured the 10% MAC option and sought to postpone the implementation of the HCR by a year. Ultimately, the compromise reached on the HCR represents an improvement over the current situation and is expected to facilitate rebuilding the saury stock to Bmsy (biomass at maximum sustainable yield) by 2028. Importantly, this compromise marks progress towards developing and implementing a comprehensive MP for Pacific Saury based on a full scientific testing process called management strategy evaluation, which is expected to be adopted by the 2027 Commission meeting.

Given recent climate fluctuations and excessive fishing, the decline in saury populations has intensified, further complicating management efforts. Therefore, proactive, science-based management through its interim HCR and, subsequently, a comprehensive management procedure is crucial. To achieve this, stakeholders in the NPFC, including significant fishing nations and citizens who enjoy seafood, must prioritise conservation efforts and sustainable management practices. We all hope to see increased efforts for the Pacific Saury conservation in the NPFC Convention Area in the near future.

There’s much to celebrate today in the Indian Ocean. The gavel just dropped on the annual Indian Ocean Tuna Commission (IOTC) meeting in Bangkok, and not one but two management procedures (MPs) were adopted! As we had hoped in the preview we posted last week, IOTC members came together to chart a course for the future of sustainable fisheries for two priority stocks: swordfish and skipjack tuna.

The adoption of the first-ever MP, also known as a harvest strategy, for swordfish, marks a historic milestone for international fisheries. Anchored in rigorous scientific groundwork, the MP will set the first total allowable catch (TAC) for swordfish in the Indian Ocean to ensure a sustainable and healthy swordfish population, safeguarding the continued productivity of the fishery. It is designed to provide a 60% probability that the swordfish stocks will achieve the target reference point (TRP), which is set at the adult biomass that will support maximum sustainable yield (SBMSY) between 2034-2038. The MP aims to maximize the average catch while balancing the stock’s continued stability and ensuring a high probability of avoiding the limit reference point (LRP) of 40% SBMSY. The first MP-based TAC will be implemented in 2026, following an agreement on an allocation arrangement no later than 2025.

Adopting an MP for a non-tuna species managed by one of the five tuna Regional Fisheries Management Organizations (RFMOs) is a significant milestone. It demonstrates the IOTC’s commitment to sustainable fishery management and underscores the importance of a proactive approach to managing already healthy fish stocks. Now, managers in the Atlantic and Pacific oceans should follow this development by adopting harvest strategies for the other swordfish populations around the world.

In tandem with a new harvest strategy for swordfish, the IOTC has also adopted a comprehensive, fully specified MP for skipjack tuna. The skipjack MP targets at least a 50% likelihood that skipjack stocks will be at or above 40% of the unfished level (SB0) by 2034-2038, which is roughly equivalent to a 90% chance of being above the biomass that would support MSY. The MP also commits to keeping the skipjack stock levels above the limit reference point of 20% of SB0 “at all times.” This will ensure that the stock is never overfished. Since the 2016 HCR was used to set the skipjack TAC for 2024-26, the MP will used to set the TAC starting in 2027.

Furthermore, IOTC has tasked the Scientific Committee (SC) with incorporating a multi-species framework into future revisions of the MP, including consideration of fishing impacts on the marine ecosystem (i.e., associated and non-target species – marine turtles, marine mammals, seabirds, sharks and other fish species), a move towards ecosystem-based fisheries management (EBFM).

An EBFM perspective recognizes the interconnectedness of marine species and the cumulative effects of fisheries on ecosystem health. By adopting this comprehensive approach, IOTC is advancing towards ensuring the sustainability of individual species like skipjack tuna and swordfish while holistically safeguarding marine biodiversity.

The work doesn’t end with swordfish and skipjack; albacore tuna is the next MP on the horizon for the Indian Ocean, scheduled for adoption in 2025, and the development of an MP for overfished yellowfin tuna needs to be reinvigorated. In addition, the crucial topic of allocation will also be a focus, ensuring equitable and sustainable distribution of tuna resources. The TACs based on the 2016 skipjack HCR have been exceeded by up to 30% every year since adoption, and that’s likely to continue under the new skipjack MP unless IOTC urgently resolves its longstanding allocation deadlock.

Although initial efforts to advance the development of an MP for blue sharks fell short, the IOTC Scientific Committee will have an opportunity to provide important input during their upcoming December deliberations.

As we close a pivotal week for international fisheries, the collaborative milestones achieved for swordfish and skipjack tuna exemplify a steadfast dedication to sustainable fisheries management using MPs and hold the promise of what’s to come.

In the world of fisheries management, certain moments stand out as pivotal — opportunities to redefine our approach to ocean stewardship and secure a more sustainable and biodiverse marine environment. The upcoming Indian Ocean Tuna Commission (IOTC) meetings in Bangkok, Thailand, are poised to be one such moment, with the opportunity to set precedents for the management of swordfish and skipjack tuna fisheries, as well as lay the groundwork for locking in a sustainable future for sharks. Management procedures (MPs), also known as harvest strategies, are at the heart of each of these potential advancements.

Swordfish Management: A Pioneering Move

The IOTC’s anticipated adoption of an MP for swordfish would be a significant breakthrough, representing three “firsts.” If the Australian proposal passes, the MP will set the first-ever catch limit for swordfish in the Indian Ocean, starting in 2026. It would also be the first MP adopted for swordfish worldwide and the first MP for any non-tuna species managed by one of the five tuna Regional Fisheries Management Organizations (RFMO).

This initiative recognizes the critical importance of comprehensive MPs in managing the complexities and uncertainties of marine fisheries. Given the healthy status of the swordfish population in the Indian Ocean, it emphasizes the value of implementing an MP while fish stocks are still at target levels. As such, it is crucial for the IOTC to adopt the MP for swordfish without delay to ensure the continued vitality and sustainability of this resource.

Sustainable Management for Skipjack Tuna

IOTC has faced challenges in effectively managing skipjack tuna fisheries. Since adopting a harvest control rule (HCR) in 2016, annual catch limits have been consistently surpassed. A key roadblock has been the difficulty in agreeing on catch allocation among member states. To improve the scientific basis for management, the European Union has proposed an MP that builds upon and upgrades the current HCR to a fully specified MP, offering a comprehensive and transparent approach to managing skipjack tuna.

The proposed MP outlines the management objectives, the decision rule for calculating the total allowable catch (TAC), and the process for handling exceptional circumstances – rare and unforeseen events that the MP is not designed to manage.

IOTC should adopt an MP for skipjack tuna, requiring a 70% likelihood that the fishery’s status will align with management objectives to ensure the stock is neither overfished nor subject to overfishing, important since skipjack plays such a vital role in the marine ecosystem as both predator and prey.

Once implemented, a fully specified MP will combine meticulous scientific analysis with strategic policy enhancements to ensure the long-term viability of the skipjack tuna fishery.

Extending the Horizon to Sharks

In addition to the progress anticipated for swordfish and skipjack, Maldives and Pakistan have submitted a proposal to broaden the IOTC’s management of sharks. The proposal calls for the development of reference points for priority shark species, key elements that contribute to creating an MP in the future. It also specifically calls for a TAC for blue sharks, which can be most effectively set by an MP. This proposal also highlights apex predators’ vital role in marine ecosystems and their vulnerability to overexploitation—a move that underscores the species’ ecological significance and susceptibility to overfishing.

Widening IOTC’s scope by adopting this proposal would usher in several promising developments. It marks the continued progression of implementing specific actions designed to secure shark populations’ future health and sustainability. It sets the stage for an expanded application of MPs to sharks and other non-target species. It also creates an opportunity to craft comprehensive MPs that reflect the complex interplay among marine species and their roles within their ecosystems.

Looking Forward

As we look forward to the critical discussions at the IOTC meetings, it’s important to note the significant role played by the 8th Session of the Technical Committee on Management Procedures (TCMP), which is scheduled to meet on May 10-11, just before the main annual meeting on May 13-17. The TCMP will evaluate and recommend the final set of candidate MPs for swordfish and skipjack tuna, serving as an essential science-management dialogue forum. This moment is historically significant, marking possibly the first instance where a tuna RFMO is set to adopt two separate MPs within the same meeting—one for swordfish and another for skipjack tuna.

The push for these advancements is bolstered by support from a wide spectrum of organizations and stakeholders, highlighting a consensus around the urgency and necessity of advancing MPs. Institutions such as The Pew Charitable Trusts, the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF), the International Seafood Sustainability Foundation (ISSF), Bumblebee Foods, Europêche, and the NGO Tuna Forum—have all signaled their backing, underlining the collective priority within the IOTC framework to progress MPs.

As stakeholders convene in Bangkok, we advocate for IOTC members to grasp this opportunity and commit to implementing comprehensive management approaches for these key species. Such action would affirm their commitment to maintaining robust and productive fisheries for the future.