October 30, 2024

When I first delved into the world of harvest control rules and harvest strategies in 2011 during my time with WWF as their global tuna lead, I saw it as a critical opportunity to ensure sustainable fisheries. At the time, except for Southern Bluefin Tuna, none of the tuna RFMOs had established effective harvest strategies, despite the clear benefits they offered. It was a moment where the scientific community, NGOs, and some in the industry began to rally around this concept, recognizing that pre-agreed frameworks for managing fishing effort could mitigate the volatility and short-term pressures that often dominate RFMO negotiations.

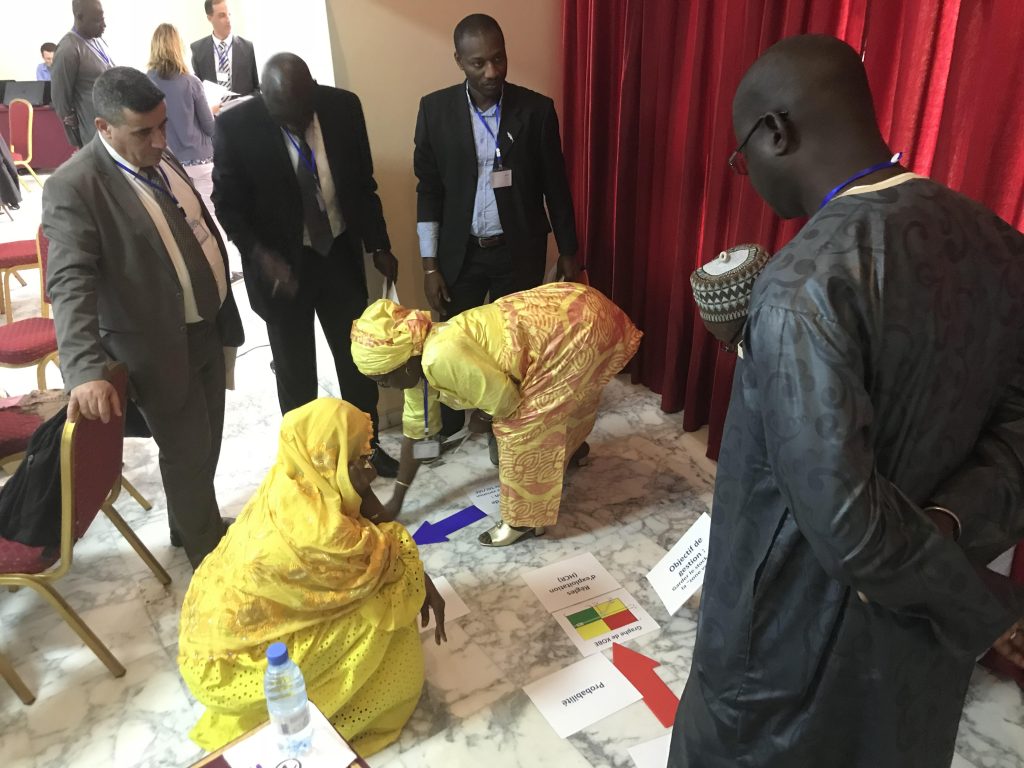

A key challenge we encountered early on was the lack of understanding among stakeholders, particularly those outside the scientific realm. Harvest strategies were often perceived as a ‘black box’ solution—complex and intimidating. This is where capacity building became essential. Working on the Common Oceans Project, we hosted a series of workshops, using interactive tools to demystify harvest strategies and get participants actively involved in shaping their development. I remember one workshop vividly: participants were surprised to learn that there isn’t always a single “right” answer when mapping out a harvest strategy. Different components, such as reference points and harvest control rules, can be arranged in multiple ways, depending on the needs of specific fisheries. This flexibility is one of the greatest strengths of harvest strategies, allowing them to be tailored to the unique challenges each fishery faces.

While we’ve made significant progress—tuna RFMOs have adopted several harvest control rules in recent years—the true challenge lies ahead: effective implementation. In the Indian Ocean, for example, despite adopting harvest control rules for skipjack tuna, we’ve seen significant non-compliance with recommended catch limits. Moving forward, compliance isn’t just about enforcement. It’s about fostering goodwill, ensuring all stakeholders feel invested in the long-term goals of sustainable management, and developing fair allocation systems that work for everyone involved.

Monitoring and enforcement will also play a crucial role. The adoption of advanced technologies, like electronic monitoring systems and automated data analytics, will be essential to ensuring that harvest strategies work in practice. We’ve already seen fisheries adopt management procedures that integrate such tools, and it’s a model that will need to be expanded globally.

The journey of implementing harvest strategies over the past decade has been transformative. In 2014, I was thrilled to see mainstream media in the UK publish pieces on the need for harvest control rules and the European retailers demanding this—something unheard of when I began this work. Today, many of our GTA partners instantly understand the value of these strategies. This is a credit to all the capacity building that has happened. However, as we look ahead, ensuring robust compliance and continued capacity building will be critical to their long-term success.

At the Global Tuna Alliance (GTA), our global supply chain partners are deeply committed to pushing for progress in this area. Over the next five years, we will leverage our partnerships to advocate for the effective uptake and critical implementation of harvest strategies across all tuna RFMOs, ensuring that our tuna fisheries remain sustainable for future generations.

About the Author: With 20 years of experience in fisheries and marine conservation, Daniel Suddaby has a deep passion for the ocean, marine life, and sustainable fishing practices. He is an expert in tuna, advocacy, and sustainable market tools that drive change in fisheries and seafood supply chains. Prior to joining the GTA, Daniel founded and led the Tuna and Distant Water Fisheries Program at Ocean Outcomes, building effective relationships with longline tuna and supply chain companies to incentivize transformation through tools such as the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) Fishery Improvement Projects. Previously, Daniel spent six years as the Deputy Leader of the World Wild Fund for Nature’s (WWF) global fisheries initiative, leading global engagement in tuna fisheries and advocacy in all Regional Fisheries Management Organisations (RFMOs), and providing strategic direction to WWF International on seafood engagement. He also has experience as a Senior Fisheries Certification Manager for the MSC.