I write this from Seville, Spain where the gavel has just dropped on the annual meeting of the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT). After a long 8 days of negotiations, we’ve ended with both high notes and disappointments for management procedure (MP) development and implementation at ICCAT.

First, the high notes:

The Commission adopted an MP for western Atlantic skipjack tuna as the first dedicated management for the stock. The effort was led by Brazil on both the science and management sides, having been initiated by the renowned Brazilian scientist, Dr. Fabio Hazin. Brazil championed the proposal in Seville, with the United States as a co-sponsor, and the final version will set future total allowable catch limits (TACs) for the stock in 3-year blocks. The results of the management strategy evaluation (MSE) were presented in www.HarvestStrategies.org’s Shiny App, Slick, for ICCAT member review and consideration when selecting the final MP. Western skipjack is a unique fishery at ICCAT as more than 90% of the catch is caught by one fleet, the Brazilian baitboat fishery. As a low bycatch handgear fishery, now with a long-term MP in place, the fishery can proudly say they’re a world leader in sustainable management.

Next, an exceptional circumstances protocol (ECP) was adopted for North Atlantic swordfish as an annex to the MP adopted last year, completing the MP. Canada’s proposal outlines the rare or unforeseen scenarios that could warrant reconsidering the application of the MP, as well as a decision tree for how to handle related deliberations on both the science and management sides. This ECP is a bit more flexible than prior ones adopted by ICCAT, largely due to this year’s experience with the exceptional circumstances review for ICCAT’s most iconic and controversial species, Atlantic bluefin tuna.

Which brings us to the hottest topic – and one of the disappointments – of ICCAT 2025:

This year marked the end of the first management cycle of the Atlantic bluefin tuna MP adopted in 2022, a huge step forward for the species that had once been the posterchild of overfishing, leading to ICCAT being called “an international disgrace” and a travesty in fisheries management.” In addition to running the adopted MP to set the western and eastern TACs for the next management cycle (2026-28), ICCAT scientists also did their standard annual check for exceptional circumstances. And that’s where things got more complicated.

New science using genetic analysis methods produced the first census estimate of the size of the western stock that spawns in the Gulf of Mexico. The scale of the western population size was one of the most influential uncertainties in the MSE, so having a point estimate represented a major step forward for bluefin science. However, ICCAT scientists could not agree on whether the new information constituted an official exceptional circumstance, as laid out by the ECP, since the new point estimate of stock biomass falls within the range considered in the original MSE. Nonetheless, ICCAT scientists did a light revision of the MSE and subsequently updated the original MP, providing two separate MPs and associated TACs to the Commission as the scientific advice – BR, the originally adopted MP, and BR*, the new revised MP.

This unfortunately opened the door to extensive negotiations here in Seville on the MP and how to implement it. After days of debate on 10 separate formal proposals, ICCAT ended by continuing to operate under the originally adopted BR MP, but with incomplete implementation. The adopted eastern measure implements the MP-based TAC (near final draft here). However, in the West, the new measure sets a TAC 20% higher than allowed under the originally adopted MP, with an extra 100 t transfer from the East to the West to use for bycatch in the vicinity of the West/East management boundary. The final TAC represents a 17% increase in the western TAC, counter to the MP.

This is not how the MP process is supposed to work. First, the ECP for Atlantic bluefin tuna is very clear. The first step is to answer the question, “Is there evidence of an exceptional circumstance?” If the answer is yes, then further investigations should be considered, such as revising the MP. But ICCAT scientists did the revision before first answering the question. This led to the scientific advice including two separate MPs with two separate sets of 2026-28 TACs, complicating Commission negotiations. Second, an MP should be implemented fully or it jeopardizes the expected performance and ability to achieve management objectives. The sanctioned 20% western overage was chosen as the highest level that can be taken in the western area without triggering an exceptional circumstance. However, prior MSE testing found that a 20% overage would cause the MP to fail to achieve the Safety management objective, resulting in a higher than agreed upon risk of breaching the limit reference point. Thankfully, there is an MP review scheduled for the next few years that provides an opportunity to get back on course with a bluefin MP that is likely to achieve Commission objectives.

The other disappointment was the inability to pass the European Union’s proposal to adopt management objectives for North and South Atlantic blue sharks. Nevertheless, there was support for the two stocks’ MSEs to start in 2026, building on progress to date, including that made at the Global Blue Shark MSE workshop that we co-hosted last month.

As the gavel drops on this year’s annual meeting, ICCAT has a lot to be proud of, with MPs adopted for 5 of its key stocks and MSEs in process for 6 additional stocks. But MPs are not just paper rules. It’s critical to not only adopt them, but also to fully implement them. To not just set the rules but to continue to stick to them, whether the MP calls for increasing or decreasing fishing. It is notable that this was the first year that an ICCAT MP called for a TAC decrease, and ICCAT didn’t implement it. As ICCAT continues to modernize and improve the efficiency and effectiveness of its management through the MP approach, members need to recommit to preventing politics and short-term catch desires from infiltrating and compromising the MSE-based MP process.

At its annual meeting last week, the General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean (GFCM) secured the first international harvest strategy adoption of 2025. They selected a harvest control rule (HCR) for blackspot seabream in the Alboran Sea that had been tested with management strategy evaluation (MSE) and is expected to meet or exceed the Commission’s rebuilding objective. The seabream stock is critically depleted, at just 5% of its unfished level and well below the agreed limit reference point, so adoption of a long-term, science-based management plan is an important step forward.

The good news is that the most precautionary HCR was adopted (specifications in image), and it is projected to grow the stock above the limit reference point by 2030 with greater than 50% probability and achieve full recovery to the target level by 2045 with 91% probability. The bad news is that the two parties that fish the stock, Morocco and the European Union, could not agree to immediate implementation of the rule, accepting only a 56% reduction in catch for 2026 to 49.1 t rather than the 3.9 t limit dictated by the HCR. This phased-in HCR application may be ok, but it was not tested by the scientists, so it is likely that it will delay recovery and may risk the success of the measure. Still, adoption is a positive step, and the proper implementation will be reconsidered at the 2026 annual meeting. Once properly implemented, the HCR will represent GFCM’s first-ever rebuilding plan, a momentous step for a body where more than half of the assessed fish stocks are classified as overfished.

The blackspot seabream HCR joins the GFCM’s first two HCRs adopted last year for Adriatic sardines and anchovies, showing impressive progress in harvest strategy development. Those two stocks also provided GFCM with clear evidence about the utility of this approach, as the new catch limits for 2026 followed the outputs of the HCRs and were adopted with minimal discussion. An ambitious workplan aims to advance HCRs for an additional 11 stocks over the next 2 years, but only half of those intend to include thorough MSE testing in the initial development. The three HCRs adopted to date were developed using MSE, so the potential move away from this testing at GFCM is concerning. Untested HCRs cannot be reliably expected to achieve management objectives for the stock and fishery.

Red shrimp in the Ionian Sea and Strait of Sicily, in addition to dolphinfish, are prioritized for MSE testing in 2026. Rapa whelk in the Black Sea is also on the list, but given it’s an invasive species, the environmental benefits of an MSE-tested harvest strategy are a bit more opaque. If these 4 stocks are the focus for 2026, hopefully the other 7 stocks in the MSE workplan will benefit from more robust MSE testing in 2027-28.

With its first three HCRs adopted in just 13 months, GFCM has a lot to be proud of. Going forward, the body should continue to prioritize rigorous MSE testing since MSE is central to securing many of the benefits of the harvest strategy approach. Further, GFCM should evolve toward adoption of fully specified management procedures, which include not just an HCR but also the data collection and assessment methods used to drive the HCR. This ensures consistent application of the HCR and therefore greater confidence in the expected performance.

Esther Wozniak, a senior manager for The Pew Charitable Trusts’ international fisheries program, said:

“Blackspot seabream is severely depleted and in need of immediate action. Although GFCM members adopted a precautionary, science-based approach to recover the species, they postponed its implementation and set fishing limits for 2026 that are much too high, and are based on short-term motivations rather than their newly adopted rules. This decision will delay recovery of this important fishery and may complicate future steps to implement stronger catch limits.

For several species, GFCM members have a track record of allowing years of overfishing before reaching agreement to rebuild fisheries. This has recently begun to change, which is why the decision to delay implementation on blackspot seabream is disappointing. Only continued, cooperative efforts to implement harvest strategies can guarantee the future health of all of GFCM’s valuable and ecologically important species.”

In mid-October 2025, scientists from around the world gathered in Rome, Italy, for a three-day technical workshop on Global Blue Shark Management Strategy Evaluation (MSE). Hosted by The Ocean Foundation and The Pew Charitable Trusts, with key support from the FAO Common Oceans Program, Oceankind, and the Paul M. Angell Family Foundation, the event aimed to build progress toward sustainable, adaptive management procedures (MPs) for highly valuable blue shark (Prionace glauca) stocks worldwide.

The case for MSE

Blue sharks are the most commonly landed shark species in international waters and a key target for numerous fisheries, with worldwide blue shark landings estimated to be worth more than $400 million USD. However, their current management relies on stock assessments that are often hindered by data limitations and other uncertainties. Developing and implementing MSE-tested management procedures (MPs), also known as harvest strategies, that are robust to key uncertainties is therefore an important step towards ensuring responsible and adaptive management of these stocks.

The workshop on Global Blue Shark MSE was attended by leading experts in MSE and blue shark science, representing all four regional fisheries management organizations (RFMOs) that manage fisheries that catch the species: the Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission (IATTC), the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC), the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT), and the Indian Ocean Tuna Commission (IOTC). The workshop was timely, as both ICCAT and IOTC have begun initiatives to develop MSE-tested MPs for their respective blue shark stocks.

Setting the stage: common ground and shared challenges

The workshop kicked off with welcoming remarks from Grantly Galland (The Pew Charitable Trusts), Shana Miller (The Ocean Foundation), and Joe Zelasney (FAO), who set an inspiring tone and outlined the goals for the days ahead. First up on the agenda were regional overviews of current blue shark science and management efforts in the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans, provided by leading scientists from each basin. These discussions highlighted that, across regions, existing stock assessments for blue shark are often hindered by data-poor conditions and significant uncertainties (e.g., conflicting CPUE indices and unreliability in historical catch data).

With these challenges in mind, as the day progressed, the group discussed the utility and feasibility of implementing an MSE approach for blue shark management. Presentations reviewed preliminary MSE work for blue shark conducted to date at ICCAT for the North Atlantic stock and highlighted the IOTC’s request to initiate blue shark MSE efforts. Participants discussed key considerations when developing operating models (OMs) to support potential MSE efforts, including regional uncertainties that should be represented across the suite of OMs. They also touched on the types of MPs that might be most appropriate for addressing the unique management challenges and population dynamics of these widely distributed sharks, which are often co-caught with other target species. Conversations stressed the importance of involving managers and stakeholders early in MSE processes to increase transparency, collaboration, and shared motivation for the eventual adoption of an MP.

Getting hands-on

Day Two initiated dedicated, highly technical hands-on sessions. The day began with a guided demonstration of the openMSE software framework, an open-source modeling tool widely used in RFMO MSE efforts, by its creators at Blue Matter Science. Experts from Blue Matter Science guided workshop participants through the entire MSE process using openMSE, from building OMs and defining performance indicators (PIs) to designing candidate MPs and evaluating their ability to achieve management objectives via the MSE feedback loop. This demonstration provided the foundation for group breakout sessions, where participants were organized based on their region of expertise. Breakout groups worked with real data from five blue shark stocks (North/South Pacific, North/South Atlantic, Indian Ocean) to create preliminary OMs, craft custom PIs, and explore hypothetical candidate MPs using the openMSE framework.

The final day of the workshop included a presentation on standard visualization tools for presenting MSE outcomes, featuring a demonstration of the Slick app for producing figures such as timeseries and tradeoff plots to convey candidate MP performance. Regional breakout groups then reconvened to finalize their modeling efforts and create Slick objects to visualize their work. The workshop culminated in final breakout group presentations, where each region showcased their products from the last two days, including their thought processes when developing hypothetical OMs and candidate MPs for blue sharks. Groups also offered suggestions and reviewed the procedural steps that would be required for progressing these efforts at their respective RFMOs. Comprehensive modeling work and summary presentations were completed for all five global blue shark stocks.

Building blocks towards sustainable management

This workshop offered a rare and invaluable opportunity to bring together experts from across ocean basins, providing a venue to discuss shared knowledge and challenges related to effective blue shark management. While only ICCAT and IOTC have committed to date to pursuing MSE-tested MPs for blue sharks, the preliminary technical work conducted last month in Rome has laid important groundwork for all stocks across all RFMOs. This progress toward the development and adoption of sustainable management procedures marks a key milestone for the long-term sustainability of this ecologically important species around the world.

For even more information, the FAO published a news story on the workshop, and a full workshop report will be available in the coming months.

The EU, Norway and UK face a pivotal moment for the management of a key Northeast Atlantic forage fish

North Sea herring, a small pelagic forage fish, has long been a cornerstone of European fisheries and is vital to both the marine ecosystem and the coastal economies that depend on it. But, like other internationally-shared fisheries in the Northeast Atlantic such as those for mackerel, blue whiting and Atlanto-Scandian herring, the North Sea herring fishery also has had challenging periods in its management, including historic periods of overfishing. However, an upcoming negotiation could mark a monumental shift in how North Sea herring and other key fisheries are managed, both in terms of sustainability and with regard to their important role in the marine ecosystem.

Fisheries managers can adopt a new long-term management strategy (LTMS) for North Sea herring in two planned rounds of trilateral meetings among the European Union, Norway and the United Kingdom, scheduled in the weeks of 27 October and 17 November. This LTMS – the regional term used in the Northeast Atlantic for harvest strategy or management procedure – would include a harvest control rule (HCR) to set annual catch limits. If followed, these limits could lead to sustainable management for many years to come. The strategy would set clear benchmarks and rules for future changes in allowable catch while recognizing herring’s crucial role in the marine ecosystem. This plan would ensure that the fishery not only meets long-term human demand but also accommodates the needs of key predators such as seabirds.

State-of-the-art science backs the North Sea herring management proposal

Nearly two years of collaborative scientific work by the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES) underpins the development of a North Sea herring harvest strategy, work that has been scientifically tested using a process called management strategy evaluation (MSE). This tool tests a variety of HCRs using computer simulations to find out which ones can best achieve the desired long-term sustainability and precautionary objectives for the fishery while providing predictable and high annual catches for the fishing sector, markets and consumers.

At the request of the three negotiating Parties, an ICES Workshop on Management Strategy Evaluation for North Sea Herring convened in early 2024 to conduct an MSE to test the ability of several harvest strategies in achieving various management objectives. The MSE process covered a range of ecological scenarios and reflected key scientific and management uncertainties to help determine the best possible management approach.

The MSE tested HCRs under a plausible range of natural conditions. These incorporated biological parameters for the species based on an ecosystem model that included a spectrum of predator-prey dynamics and examined scenarios that reflect natural variability and potential environmental influences on the productivity of herring. By integrating these ecological considerations, ICES scientists provided informed evaluation and advice to the Parties on a management framework that acknowledges herring as part of a dynamic ecosystem.

A balanced harvest strategy could help secure North Sea herring’s sustainability

With several science-based options now on the table, managers need to adopt their preferred harvest strategy and use it to set a total allowable catch (TAC) limit for 2026. One of the options, known as Management Strategy 3 (MS3), has gained traction among the parties. And while it isn’t the most precautionary option available, it does offer a good balance of stock health, total allowable catch and acceptable levels of stability and risk. If implemented successfully, it would help to ensure future sustainability.

Over the summer, the Parties jointly asked ICES to reissue their annual catch advice for herring based on the particular management parameters of MS3. But the coming weeks are pivotal. By adopting this harvest strategy, including it in their publicly available Agreed Record of negotiations and using it to set their future catch limits, managers can lock in a transparent, scientific and rule-based framework that provides predictability and stability for operators in the region and takes ecological considerations into account.

But adopting the harvest strategy isn’t enough. To really succeed, the Parties should also develop what is known as an Exceptional Circumstances Protocol. This would set clear parameters for whether and when the LTMS should be re-evaluated while allowing adaptability in cases of changes on the water.

The North Sea herring MSE process shows what’s possible when scientists, managers and stakeholders work together. Now, with a clear evidence base and consensus within reach, managers have a rare opportunity to set a new management precedent and secure the future of the iconic North Sea herring fishery. They can then chart a path forward for other important Northeast Atlantic fisheries such as mackerel and Atlanto-Scandian herring.

Ashley Wilson works on The Pew Charitable Trusts’ international fisheries project.

The www.HarvestStrategies.org team is thrilled to announce the launch of a new course series: “Management Procedures for Sustainable Tuna Fisheries,” developed in partnership with the FAO eLearning Academy. There are five educational modules that cover topics related to management procedures (MPs), from setting the vision for the future of the fishery with management objectives, to testing candidate MPs using management strategy evaluation (MSE), to implementation using the MP feedback loop.

The five courses include:

Together, the courses amount to approximately 6.5 hours of learning. Once completed, users can take a final test to earn an FAO eLearning Academy digital certification badge, which can lead to expanded employment opportunities, among other benefits.

The course is designed for a wide range of learners, including fishery managers, fishery scientists, industry professionals, environmental stakeholders, and others. It’s relevant to both tuna and general RFMOs, as well as domestic fisheries. The open-source, free-to-use content can also be used by colleges and universities for academic training. All that is needed is an FAO eLearning Academy log-in (Click here to register for free!).

While the series is currently available only in English, Spanish and French versions will be launching within the next few months. For learners eager to apply their new knowledge to an MP development process close to home, we are pleased to offer a limited number of follow-up, customized, live sessions, tailored to the audience’s interests, either online or in-person. Please email info@harveststrategies.org to learn more!

This course has been many years in the making, and we would like to give a tremendous thank you to our project sponsors and partners, most notably the Common Oceans Tuna Fisheries Project, which is funded by GEF and implemented by FAO. The Pew Charitable Trusts and International Seafood Sustainability Foundation (ISSF) also helped with content development and review. We are also indebted to our Project Advisory Committee and a focus group of esteemed fisheries managers, scientists, and industry representatives whose review and input greatly improved the materials.

Please visit the FAO eLearning Academy to take one – or ideally, all! – of the courses to deepen your understanding of management procedures and strengthen your ability to engage meaningfully in the development and adoption process. It will help to ensure your priorities are reflected in the process, and you might even have a little fun along the way!

Stay tuned for an announcement about our next quarterly webinar, which FAO will host as the official launch of the course!

The Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission (IATTC) convened for its annual meeting in Panama City last week. At the start of the year, the plan was to adopt harvest strategies for both bigeye and Pacific bluefin tuna at the Commission meeting, which would have revolutionized tuna management in the eastern Pacific. Unfortunately, the bigeye tuna management strategy evaluation (MSE) work wasn’t complete, and the Pacific-wide bluefin regulatory body was unable to reach consensus on selection of a harvest strategy when it met in July, precluding IATTC from adoption for both stocks in Panama. However, important groundwork was laid at the meeting to advance harvest strategies for several of its valuable stocks in the coming year.

A new measure was adopted for tropical tunas, which commits to finalizing the bigeye MSE in 2026 to enable harvest strategy adoption next year. To facilitate the process, the new Working Group on MSE will meet three to four times between now and then to discuss management objectives and provide feedback and direction on the preliminary performance results of the candidate harvest strategies being considered.

The MSE for Pacific bluefin is complete, and governments are selecting among a handful of candidate harvest strategies projected to meet objectives. To advance the discussions toward consensus, IATTC members agreed to hold an intersessional meeting of the joint working group with the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC) in early 2026, which is a very important step toward adoption.

South Pacific albacore is currently unmanaged in the eastern Pacific, but that could soon change as terms of reference were agreed upon for a new joint working group with WCPFC on management of the stock. WCPFC is slated to adopt a harvest strategy for South Pacific albacore later this year, and this new working group strives to develop complementary management for the eastern part of its range.

IATTC members also agreed to establish a working group on dorado, also known as mahi-mahi. This commercially and recreationally targeted species is highly valued, yet to date lacks international management in the Pacific and beyond. IATTC scientists completed an MSE for the stock in 2019, but it was never used for management. This new working group will facilitate new assessment efforts and reopen the door for future development of a harvest strategy for the stock.

HarvestStrategies.org also participated in a side event hosted by the FAO Common Oceans Program, where we highlighted the educational materials we’ve developed on harvest strategies and MSE, including exciting news about our soon-to-be-released eLearning course. It’s our hope that these communication tools will provide valuable support as IATTC works to bring multiple harvest strategies across the finish line next year.

IATTC is currently the only tuna management body without a harvest strategy in place. While IATTC adopted a harvest strategy for North Pacific albacore in 2023, the output of the rule is “fishing intensity,” which cannot be implemented until converted into total allowable catch and/or effort. While that conversion was slated for agreement last year, talks have continuously stalled, and members have agreed to finish the job in 2026.

With harvest strategy adoption slated for both bigeye and Pacific bluefin, as well as agreement on how to implement the North Pacific albacore harvest strategy, 2026 is shaping up to be a milestone year for harvest strategies at IATTC!

The North Pacific Fisheries Commission (NPFC) is one of the youngest Regional Fisheries Management Organizations (RFMOs), established in 2015. Its objective is to ensure the long-term conservation and sustainable use of fishery resources in the Convention Area while protecting the marine ecosystems of the North Pacific Ocean where these resources are found.

Since 2018, I have participated in NPFC Scientific Committee (SC) meetings and its subsidiary group meetings, witnessing how the NPFC has progressed toward a science-based management framework through collaborative scientific efforts among its members. This progress is particularly evident in the stock assessment and management of two NPFC priority species—Pacific saury (Cololabis saira) and Chub mackerel (Scomber japonicus).

The NPFC SC has been enhancing its understanding and capacity to develop management strategy evaluation (MSE) for its priority species since 2019. Each year, the NPFC SC nominates and provides financial support for SC representatives to attend relevant scientific training sessions and meetings, fostering their expertise in this field. In February 2025, I was nominated and selected as an SC representative to participate in a one-week capacity building activity organized in collaboration with Blue Matter Science in Vancouver, Canada. This capacity building activity aimed to develop a stock assessment model and MSE framework for another NPFC priority species—Neon flying squid (Ommastrephes bartramii). The Small Scientific Committee on Neon Flying Squid (SSC NFS), established in 2024, is still in its early stages but is committed to developing a science-based approach to management of the species. To date, only two SSC NFS meetings have been held to assess the fishery status and evaluate data availability among NPFC members.

Before traveling to Vancouver, I reviewed the available data and confirmed that annual catch and catch per unit effort (CPUE) data were available and sufficient to support the development of a type of assessment model called a surplus production model under data-moderate conditions. This was significant since people often think of squid fisheries, like other short-live species, as data-poor. I attempted to fit surplus production models (i.e., SPiCT) to both the winter-spring and autumn cohorts of Neon flying squid, but only the model for the autumn cohort successfully met the diagnostic criteria for acceptable model performance.

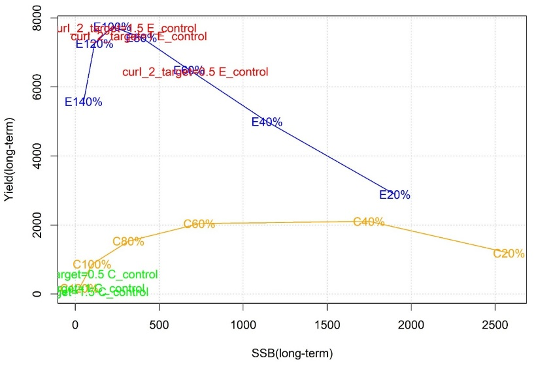

During my visit to Vancouver, I received technical guidance from Blue Matter Science scientists—Drs. Tom Carruthers, Adrian Hordyk, and Quang Huynh—to develop an MSE framework for Neon flying squid using their OpenMSE package. We constructed and conditioned an age-structured operating model (OM) in OpenMSE to align with the SPiCT-derived biomass and harvest rate estimates for the autumn cohort. Additionally, we designed catch- and effort-based harvest control rules (HCRs) to evaluate the performance of output versus input controls.

To approximate the 12-month lifespan of this species in the OpenMSE age-structured OM, we specified high mortality rates to effectively remove each cohort from the population after age-1.

Through closed-loop simulations using the OpenMSE package, we evaluated the management trade-offs between constant catch/effort HCRs and index-based empirical HCRs for the NFS autumn cohort. Our results demonstrate that effort control exhibits greater resilience than catch control, with maintaining current effort levels showing a 62.55% probability of sustaining stock biomass above current levels after 20 years while simultaneously maintaining a 62.65% probability of catches exceeding current levels.

The findings of this study are preliminary because certain input data and parameters remain to be finalized. We recommend that the SSC NFS collect and share finer catch and effort data to develop a monthly time-step OM for Neon flying squid, enabling more precise evaluation of seasonal biological and fishing dynamics. Such finer data would significantly improve in-season management assessments by allowing simulation of fisheries dynamics at finer temporal scales and better evaluation of management approaches using previous year’s data – though we note these have limited value for short-lived species since last year’s data contain no information about subsequent cohort abundance, so in-season management would be worth testing. Additionally, OpenMSE’s multi-stock modeling capability could facilitate development of a joint model integrating both autumn and winter-spring stocks to evaluate comprehensive management procedures for NFS fisheries.

Given the limited capacity within the NPFC SC, I hope established modeling packages like OpenMSE can be applied to more NPFC priority species – particularly Pacific saury and Chub mackerel – to help transition the NPFC toward modern, MSE-based management systems.