The Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission (IATTC) convened for its annual meeting in Panama City last week. At the start of the year, the plan was to adopt harvest strategies for both bigeye and Pacific bluefin tuna at the Commission meeting, which would have revolutionized tuna management in the eastern Pacific. Unfortunately, the bigeye tuna management strategy evaluation (MSE) work wasn’t complete, and the Pacific-wide bluefin regulatory body was unable to reach consensus on selection of a harvest strategy when it met in July, precluding IATTC from adoption for both stocks in Panama. However, important groundwork was laid at the meeting to advance harvest strategies for several of its valuable stocks in the coming year.

A new measure was adopted for tropical tunas, which commits to finalizing the bigeye MSE in 2026 to enable harvest strategy adoption next year. To facilitate the process, the new Working Group on MSE will meet three to four times between now and then to discuss management objectives and provide feedback and direction on the preliminary performance results of the candidate harvest strategies being considered.

The MSE for Pacific bluefin is complete, and governments are selecting among a handful of candidate harvest strategies projected to meet objectives. To advance the discussions toward consensus, IATTC members agreed to hold an intersessional meeting of the joint working group with the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC) in early 2026, which is a very important step toward adoption.

South Pacific albacore is currently unmanaged in the eastern Pacific, but that could soon change as terms of reference were agreed upon for a new joint working group with WCPFC on management of the stock. WCPFC is slated to adopt a harvest strategy for South Pacific albacore later this year, and this new working group strives to develop complementary management for the eastern part of its range.

IATTC members also agreed to establish a working group on dorado, also known as mahi-mahi. This commercially and recreationally targeted species is highly valued, yet to date lacks international management in the Pacific and beyond. IATTC scientists completed an MSE for the stock in 2019, but it was never used for management. This new working group will facilitate new assessment efforts and reopen the door for future development of a harvest strategy for the stock.

HarvestStrategies.org also participated in a side event hosted by the FAO Common Oceans Program, where we highlighted the educational materials we’ve developed on harvest strategies and MSE, including exciting news about our soon-to-be-released eLearning course. It’s our hope that these communication tools will provide valuable support as IATTC works to bring multiple harvest strategies across the finish line next year.

IATTC is currently the only tuna management body without a harvest strategy in place. While IATTC adopted a harvest strategy for North Pacific albacore in 2023, the output of the rule is “fishing intensity,” which cannot be implemented until converted into total allowable catch and/or effort. While that conversion was slated for agreement last year, talks have continuously stalled, and members have agreed to finish the job in 2026.

With harvest strategy adoption slated for both bigeye and Pacific bluefin, as well as agreement on how to implement the North Pacific albacore harvest strategy, 2026 is shaping up to be a milestone year for harvest strategies at IATTC!

The North Pacific Fisheries Commission (NPFC) is one of the youngest Regional Fisheries Management Organizations (RFMOs), established in 2015. Its objective is to ensure the long-term conservation and sustainable use of fishery resources in the Convention Area while protecting the marine ecosystems of the North Pacific Ocean where these resources are found.

Since 2018, I have participated in NPFC Scientific Committee (SC) meetings and its subsidiary group meetings, witnessing how the NPFC has progressed toward a science-based management framework through collaborative scientific efforts among its members. This progress is particularly evident in the stock assessment and management of two NPFC priority species—Pacific saury (Cololabis saira) and Chub mackerel (Scomber japonicus).

The NPFC SC has been enhancing its understanding and capacity to develop management strategy evaluation (MSE) for its priority species since 2019. Each year, the NPFC SC nominates and provides financial support for SC representatives to attend relevant scientific training sessions and meetings, fostering their expertise in this field. In February 2025, I was nominated and selected as an SC representative to participate in a one-week capacity building activity organized in collaboration with Blue Matter Science in Vancouver, Canada. This capacity building activity aimed to develop a stock assessment model and MSE framework for another NPFC priority species—Neon flying squid (Ommastrephes bartramii). The Small Scientific Committee on Neon Flying Squid (SSC NFS), established in 2024, is still in its early stages but is committed to developing a science-based approach to management of the species. To date, only two SSC NFS meetings have been held to assess the fishery status and evaluate data availability among NPFC members.

Before traveling to Vancouver, I reviewed the available data and confirmed that annual catch and catch per unit effort (CPUE) data were available and sufficient to support the development of a type of assessment model called a surplus production model under data-moderate conditions. This was significant since people often think of squid fisheries, like other short-live species, as data-poor. I attempted to fit surplus production models (i.e., SPiCT) to both the winter-spring and autumn cohorts of Neon flying squid, but only the model for the autumn cohort successfully met the diagnostic criteria for acceptable model performance.

During my visit to Vancouver, I received technical guidance from Blue Matter Science scientists—Drs. Tom Carruthers, Adrian Hordyk, and Quang Huynh—to develop an MSE framework for Neon flying squid using their OpenMSE package. We constructed and conditioned an age-structured operating model (OM) in OpenMSE to align with the SPiCT-derived biomass and harvest rate estimates for the autumn cohort. Additionally, we designed catch- and effort-based harvest control rules (HCRs) to evaluate the performance of output versus input controls.

To approximate the 12-month lifespan of this species in the OpenMSE age-structured OM, we specified high mortality rates to effectively remove each cohort from the population after age-1.

Through closed-loop simulations using the OpenMSE package, we evaluated the management trade-offs between constant catch/effort HCRs and index-based empirical HCRs for the NFS autumn cohort. Our results demonstrate that effort control exhibits greater resilience than catch control, with maintaining current effort levels showing a 62.55% probability of sustaining stock biomass above current levels after 20 years while simultaneously maintaining a 62.65% probability of catches exceeding current levels.

The findings of this study are preliminary because certain input data and parameters remain to be finalized. We recommend that the SSC NFS collect and share finer catch and effort data to develop a monthly time-step OM for Neon flying squid, enabling more precise evaluation of seasonal biological and fishing dynamics. Such finer data would significantly improve in-season management assessments by allowing simulation of fisheries dynamics at finer temporal scales and better evaluation of management approaches using previous year’s data – though we note these have limited value for short-lived species since last year’s data contain no information about subsequent cohort abundance, so in-season management would be worth testing. Additionally, OpenMSE’s multi-stock modeling capability could facilitate development of a joint model integrating both autumn and winter-spring stocks to evaluate comprehensive management procedures for NFS fisheries.

Given the limited capacity within the NPFC SC, I hope established modeling packages like OpenMSE can be applied to more NPFC priority species – particularly Pacific saury and Chub mackerel – to help transition the NPFC toward modern, MSE-based management systems.

Climate change has substantial implications for global fisheries. In fact, scientists project that related losses in fish biomass production in the coming decades will occur in many regions, including countries such as the Federated States of Micronesia and Portugal, that rely substantially on aquatic foods for their domestic protein supply. Further, climate change is already causing changes to geographic species distributions and species life histories, including aspects such as growth and reproduction, for stocks around the world.

In the face of these and other severe impacts, fisheries managers can develop and implement climate adaptive fisheries management measures including harvest strategies (HS), which are also known as management procedures. These strategies shift management of a fish stock from short-term and reactive decision-making to longer-term objectives, such as growing a fish population’s size, to support sustainable and profitable fisheries. HS are underpinned by a scientific assessment process known as management strategy evaluation (MSE), which ensures that management objectives can be met under a variety of environmental conditions. HS are also designed to help fisheries adapt to changing conditions.

To learn more about the intersection of HS and climate change, we performed a rapid review of recent peer-reviewed literature and found that:

To date, the results of this review have been shared with several RFMOs, including the North Pacific Fisheries Commission, the South Pacific Regional Fisheries Management Organisation, and the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas, and we hope that more fisheries managers will consider the results of the science in thinking through the role that harvest strategies can play in navigating the impacts of climate change to fisheries.

Dr. Emily Klein and Dr. Ellen Ward are officers working on The Pew Charitable Trusts’ conservation support and conservation science teams.

Ellen Ward, Ph.D., works with Pew’s conservation support team, where she focuses on furthering climate adaptation and resilience solutions in the U.S. and internationally.

Prior to joining Pew, Ward worked for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) as an international affairs specialist focused on climate change, water resources, and deep seabed mining, including representing the agency at negotiations of the International Seabed Authority in Jamaica. She previously worked on habitat conservation issues for NOAA Fisheries in Alaska and on water resources management for the Government of Yukon, Canada.

Ward holds a bachelor’s degree in physics from Columbia University and a master’s and Ph.D. in earth system science from Stanford University.

Emily Klein, Ph.D., leads Pew’s work to design research projects that use innovative analytical and modeling tools to improve what we know about marine and freshwater systems, and the human connections to them. She also works to advance inclusion, diversity, and equity within Pew, across our grantees, and in the natural sciences.

Before joining Pew, Klein studied the complex connections between people and nature to support future sustainability with Boston University’s Frederick S. Pardee Center for the Study of the Longer-Range Future. While there, she managed a project in collaboration with the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management to apply ecosystem models to inform decisions about sand mining for beach renourishment in offshore waters of the New England and the mid-Atlantic regions. Prior to this work, Klein employed models and other tools to support marine management and decision-making, including for marine protected areas under climate change in the Antarctic, and to investigate interactions between management and fishing communities.

Klein holds a bachelor’s degree in ecology, behavior, and evolution from the University of California at San Diego, a master’s in environmental conservation and doctorate in natural resources and earth systems science from the University of New Hampshire.

Pacific bluefin tuna make headlines in the world’s most prominent media outlets. “Overfishing causes Pacific bluefin tuna numbers to drop 96%.” “Massive tuna nets $3.1 million at Japan auction.” “Quota for big Pacific bluefin tuna to rise 50% amid stock recovery.” Next month, there is an opportunity for Pacific bluefin to earn their best headline yet: “Agreement on management procedure locks in long-term sustainability.” And that’s exactly what we hope we’ll be posting on this blog in mid-July.

In response to the decimation of the species to just 2% of its unfished level, Pacific bluefin managers called for the development of a management procedure (MP) to be tested using management strategy evaluation (MSE). The first dialogue meeting of scientists, managers, and stakeholders took place in 2018 to provide input on management objectives and other MP elements. Fast forward 7 years, and we have a final MSE, with 16 candidate MPs in the running for selection by the IATTC-WCPFC Northern Committee Joint Working Group on Pacific Bluefin Tuna (JWG) when it meets in Toyama, Japan, July 9-12. To prepare for that meeting, the JWG will host a webinar next week to review the final results and offer a Q&A session.

The key remaining decisions include:

For the TRP, we support neither the most aggressive nor the most conservative fishing rate, instead preferring a middle option to balance long-term catch and conservation.

For the ThRP, we support a level that is an adequate distance from the LRP to ensure that it is not breached.

For the LRP, we again support one of the central options that balances the tradeoffs between fishing and stock status objectives. We oppose the candidate MPs that do not include an LRP because LRPs are an essential element of all MPs, ensuring that the stock does not drop to a dangerously low level.

We do not have a position on the West:East split, but note that because the two options did not show much difference in terms of their conservation performance, a compromise between the values tested could also be considered as a viable alternative. Most importantly, the split should not prevent agreement on an MP next month.

The completed MSE represents the best available science for Pacific bluefin and provides performance results for stock status, catch, and fishery stability across a range of uncertainties related to stock productivity, fishery efficiency, and catch underreporting. By agreeing to an MP, the JWG will put the valuable stock on a path toward long-term fishery sustainability and profitability, with catches projected to increase over time for almost all candidate MPs as the stock is allowed to fully recover.

This is great news for the fishing industry and the seafood supply chain, all the way to the consumer of this coveted sushi selection. Adopting an MSE-tested MP could also open the door to for industry to secure sustainable seafood certifications, such as through the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC), increasing the bottom line for industry. Fishers will benefit from the predictability and transparency of a pre-agreed approach for setting annual catch limits, a stark contrast to the current ad hoc approach of political negotiations for 50 tonnes of quota here or 500 tonnes of quota there.

The deliberations of the following month have been in the making for almost a decade. Check back here in mid-July for the outcomes of the JWG meeting, which will hopefully pave the way for formal MP adoption in the western Pacific (at WCPFC) and eastern Pacific (at IATTC) later this year.

As a physical oceanographer, I’ve dedicated a significant part of my career, including my work with the North Pacific Fisheries Commission (NPFC), to understanding the intricate dance between our oceans and the valuable fish stocks they support. My focus has been on the challenges and impacts of climate change on the North Pacific marine ecosystem, and specifically, on its precious resource, Pacific saury.

For decades, fisheries management has often centered on regulating fishing activities. It’s well understood that fishing effort is a primary driver of changes in fish populations, and indeed, fisheries scientists continually study how fishing impacts fish biomass. However, the very foundation of this system – the marine environment itself – is also being fundamentally altered by climate change. This new reality demands a multi-faceted perspective. While the ocean environment alone cannot explain all fluctuations in fish catches, understanding its influence is becoming increasingly critical. My study aims to explore a complementary dimension: if we assume relatively constant fishing effort, how do long-term environmental variations, particularly those driven by climate change, directly influence fish abundance? This approach helps isolate and better understand the ocean’s role and, subsequently, how to better manage fishery resources, including through the development of science-based management procedures (MPs), also known as harvest strategies.

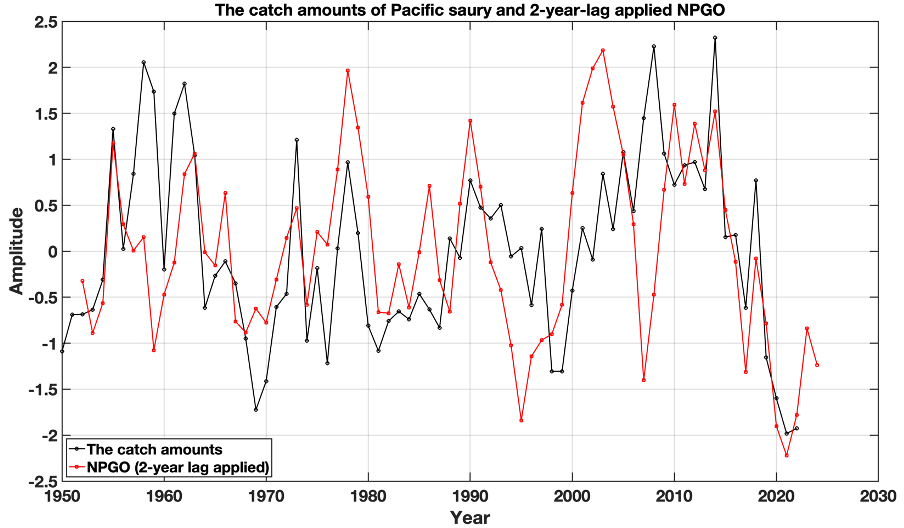

Pacific saury, once abundant at local markets and on dinner plates, has become scarce. This isn’t just an anecdote; data paints a stark picture. Figure 1 illustrates the plummeting catches of Pacific Saury in the North Pacific from 1950 to 2022, alongside the fluctuations of the North Pacific Gyre Oscillation (NPGO) Index, with a 2-year lag applied to the NPGO data. The recent decline in catch amounts (e.g., since 2010), coinciding with a similar phase shift in the NPGO index (from Positive to Negative), is a potent warning sign. This reflects the combined pressures of escalating climate change impacts and ongoing fishing activities, among other anthropogenic factors.

While large-scale climate phenomena like El Niño are well-known, the North Pacific has its crucial indicators, such as the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) and the North Pacific Gyre Oscillation (NPGO), which influence sea surface temperatures and marine ecosystems. By isolating the environmental component (under the assumption of stable fishing effort), my study revealed that the NPGO appears to wield a more decisive influence over the fluctuating fortunes of Pacific saury, as visually suggested in Figure 1.

How does an ocean-wide pattern like NPGO affect a specific species? These large-scale climate patterns influence major ocean currents, which serve as both highways and barriers for marine life. They also alter the distribution and abundance of phytoplankton and zooplankton – the primary food source for forage fish species like Pacific saury. Consequently, we’re seeing shifts in Pacific saury’s migration patterns. Recent increases in sea surface temperatures, a hallmark of climate change, are contributing to the shifting of Pacific saury fishing grounds further east as the fish seek suitable temperatures and feeding opportunities in a rapidly changing ocean. These NPGO-influenced shifts and broader warming trends can impact migratory routes, spawning times, and the suitability of traditional feeding grounds.

Perhaps the most striking discovery from my study is the predictive power inherent in the NPGO’s patterns when analyzed alongside Pacific saury catch data, under the assumption of relatively consistent fishing effort. As illustrated in Figure 1, a remarkably strong correlation emerged: specific shifts in the NPGO index can foreshadow changes in Pacific saury catches approximately two years in advance.

It’s an important question whether these observed shifts in saury linked to NPGO are solely due to its natural variability (e.g., ENSO, PDO, and NPGO) or if they are being exacerbated by broader climate change. While my study focused on the statistical relationship between NPGO phases and saury catch/distribution, it’s widely acknowledged that the North Pacific is experiencing significant warming, a trend primarily driven by climate change. This broader warming trend, particularly in traditional saury fishing grounds, undoubtedly interacts with natural climate patterns like the NPGO. Some scientific literature even suggests that climate change itself might influence the behavior and variability of these large-scale oscillations. Therefore, it is plausible that both the inherent cyclical nature of the NPGO and the overarching impacts of climate change are intertwined factors contributing to the observed changes in Pacific saury.

Regardless of the precise balance of these drivers, the two-year lead time offered by the NPGO-saury relationship provides a valuable, science-based tool. It allows us to anticipate potential future fluctuations driven by these environmental shifts. This foresight is critical and can be considered alongside dedicated analyses of fishing impacts conducted by fisheries scientists, offering a precious window of opportunity to implement and refine science-driven tools, such as MPs to best safeguard Pacific saury in a changing ocean.

The NPFC is tackling these combined challenges and spearheading efforts to integrate climate change considerations into MPs and stock assessments, while also continuing to manage fishing activities. This is where studies like mine contribute – by helping to untangle the environmental threads, we can transform abstract climate risks into manageable, actionable information. This scientific foundation empowers the NPFC to develop more sophisticated and robust MPs that are designed to be resilient to the uncertainties introduced by both climate change and other pressures.

A particularly powerful tool in this endeavor is Management Strategy Evaluation (MSE). MSE is a process where scientists and managers simulate the entire fisheries system under different conditions, including environmental and climate influences (like those identified in my NPGO study). The goal is to test how well different MPs can achieve pre-agreed objectives, helping to identify management approaches that are likely to perform best, even in the face of real-world uncertainties and changing conditions. My NPGO study, for instance, can provide valuable input for the “operating models” within MSE, helping to define plausible environmental scenarios – including those driven by climate change – against which these strategies are rigorously tested.

The NPFC has made commendable progress in advancing the management and scientific understanding of Pacific saury. Key milestones include finalizing the species’ first comprehensive stock assessment in 2024, which subsequently led to the establishment of a Total Allowable Catch (TAC). Building on this, an interim Harvest Control Rule (HCR) was adopted in 2024, based on preliminary simulation testing, providing a science-based framework for TAC determination. To further enhance long-term sustainability, the NPFC has proactively established a dedicated Small Working Group on Management Strategy Evaluation for Pacific Saury (SWG MSE PS). This group, which holds regular meetings and involves invited experts, is tasked with the critical work of developing a full MSE. As this group continues its work to develop a robust MSE, it is imperative that the NPFC ensures these evaluations explicitly consider and incorporate climate-related scenarios, including the effects of ocean warming, shifting migration patterns (like the eastward trend in saury catches), and other environmental impacts such as marine heatwaves, to build truly resilient management procedures for the future.

To comprehensively understand climate change impacts, NPFC is actively strengthening collaborations with international scientific organizations like the North Pacific Marine Science Organization (PICES). NPFC also supports initiatives like the Basin-scale Events and Coastal Impacts (BECI) project, which aims to create a North Pacific Ocean Knowledge Network. Additionally, NPFC can utilize its data-sharing agreements with other regional fishery management organizations to help identify areas for joint collaboration and share best practices regarding climate-informed management procedures.

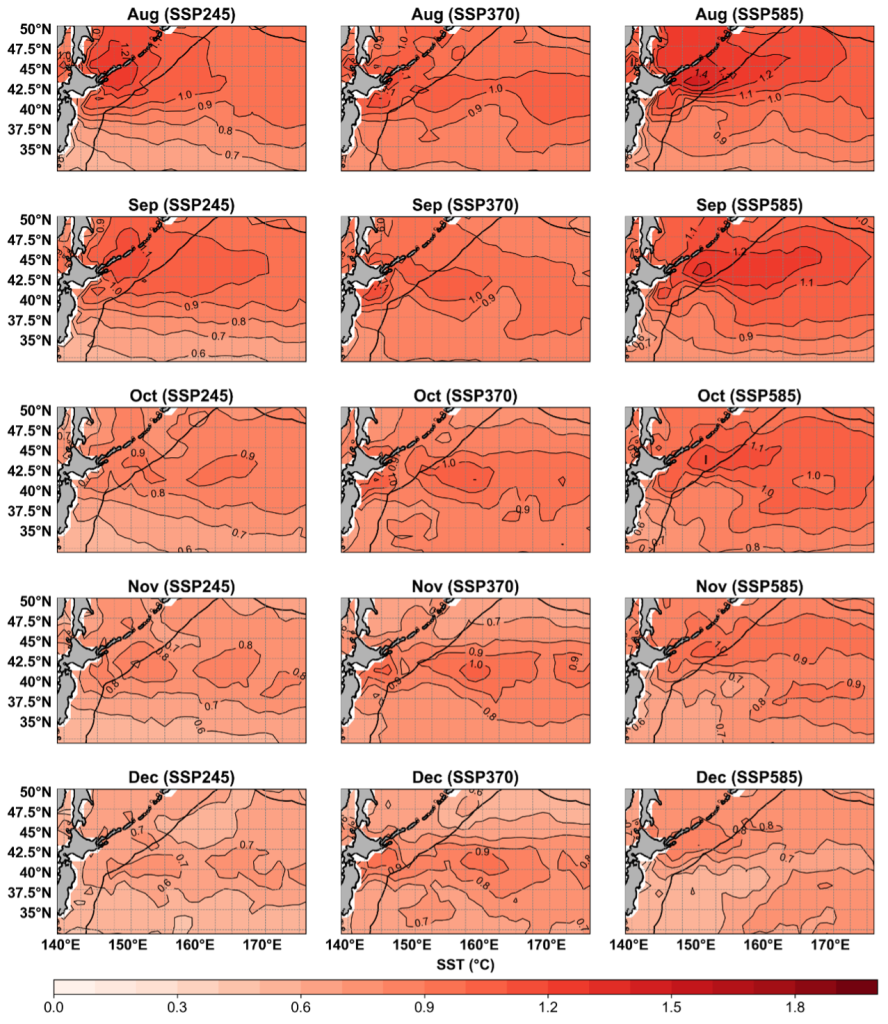

The goal is to build predictive models that can forecast future fishing grounds and stock productivity under various climate change scenarios. To illustrate the potential environmental shifts, Figure 2 displays projected changes in sea surface temperature (SST) across the North Pacific for the primary Pacific saury fishing season (August to December). These projections are based on different Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs), which are scenarios of future socioeconomic development used by climate scientists to model various levels of greenhouse gas emissions and resulting climate change.

As the maps in Figure 2 show, a consistent and concerning trend emerges across all SSP scenarios: a significant rise in sea surface temperatures is projected for the Northwestern Pacific during the peak saury fishing season. This warming is not trivial. For a species like Pacific saury, which is sensitive to water temperature, such sustained increases during their main feeding and migration period can have profound consequences. Warmer waters can alter their traditional migration patterns, potentially pushing them further eastward in search of cooler, more suitable habitats. This shift not only changes where fishing might occur but can also impact their survival rates and reduce their reproductive success by affecting spawning grounds and early life stage development. Therefore, understanding these projected SST changes across the entire fishing season under various climate scenarios is crucial for developing robust, forward-looking management strategies. While presenting multiple scenarios and months might seem like a lot of information at once, it is essential for appreciating the full spectrum of potential future conditions that NPFC’s management strategies must be prepared to address.

The journey through the North Pacific’s changing oceans reveals a stark reality: climate change presents a profound challenge, acting in concert with the ongoing impacts of fishing. Yet, there is a determined and collaborative response. My hope is that scientific endeavors, like my study on the NPGO’s influence (under specific assumptions to isolate environmental signals), provide essential building blocks for climate-adaptive MPs. These tools are about preparing for an uncertain future, ensuring management approaches are resilient and capable of safeguarding these valuable resources by considering all major drivers.

The path ahead is complex, but the commitment to science-based decision-making that considers all major drivers – both environmental and anthropogenic – offers a beacon of hope.

Dr. Jihwan Kim is an Oceanographic Engineer at Collecte Localisation Satellites (CLS) Group. He previously was a Fisheries and Data Scientist with the North Pacific Fisheries Commission.

We are pleased to announce that the www.HarvestStrategies.org host, The Ocean Foundation (TOF), has received a 2-year grant from the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) to facilitate the development and formal adoption of a management strategy evaluation (MSE) tested management procedure (MP) for South Atlantic albacore (Thunnus alalunga). The unique partnership commits funding from not just MSC, but also TOF and all five commercial fisheries with current or pending MSC sustainable seafood certification. Learn more in the official press release and explore the project page for updates and resources.

The project will support MSE development efforts led by the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT), which agreed to management objectives for the stock last year to serve as the guiding vision for a future MP. Funding will help independent MSE experts and ICCAT scientists to build the modelling framework to identify the MP options most likely to achieve the agreed objectives.

Katherine Collinson, Fisheries Certification Specialist for one of the industry partners, Tri Marine International, said, “By targeting long-term sustainability and resilience, this project will create a replicable model that enhances both compliance with MSC standards and sustainable management for the South Atlantic albacore fishery. This work will specifically advance the necessary progress of all MSC-certified South Atlantic albacore fisheries, which require the implementation of well-defined harvest control rules, like its northern stock counterpart.”

Jack Huang, Manager of Commercial, Operation & Compliance for another project partner, Tuna Alliance Inc., said, “We are honored to receive this funding, which will enable us to strengthen sustainable fisheries management and further uphold our commitment to responsible ocean stewardship. With this support, we can enhance traceability, implement advanced monitoring measures, and collaborate globally with our partners to address the impacts on marine environments, fishery resources, and habitats. As part of the seafood industry, we recognize that safeguarding our oceans is essential for the long-term sustainability of our industry and the well-being of future generations. We value this opportunity to contribute to ocean conservation and look forward to making a meaningful impact through this collaboration.”

Arthur Yeh, Executive Vice President at FCF Co., Ltd., a lead partner on the project, added, “We are extremely honored that the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) has provided us with this invaluable opportunity, granting support in our journey toward fishery sustainability. This funding is particularly crucial as it directly supports our efforts in the South Atlantic Albacore Longline Fishery, enabling us to enhance stock assessments, improve traceability, and develop a scientifically robust and reliable harvest strategy.”

We at www.HarvestStrategies.org look forward to contributing to this innovative partnership to expand the transparent, science-based, results-driven management that MPs afford to the valuable stock of South Atlantic albacore.