6 de abril de 2023

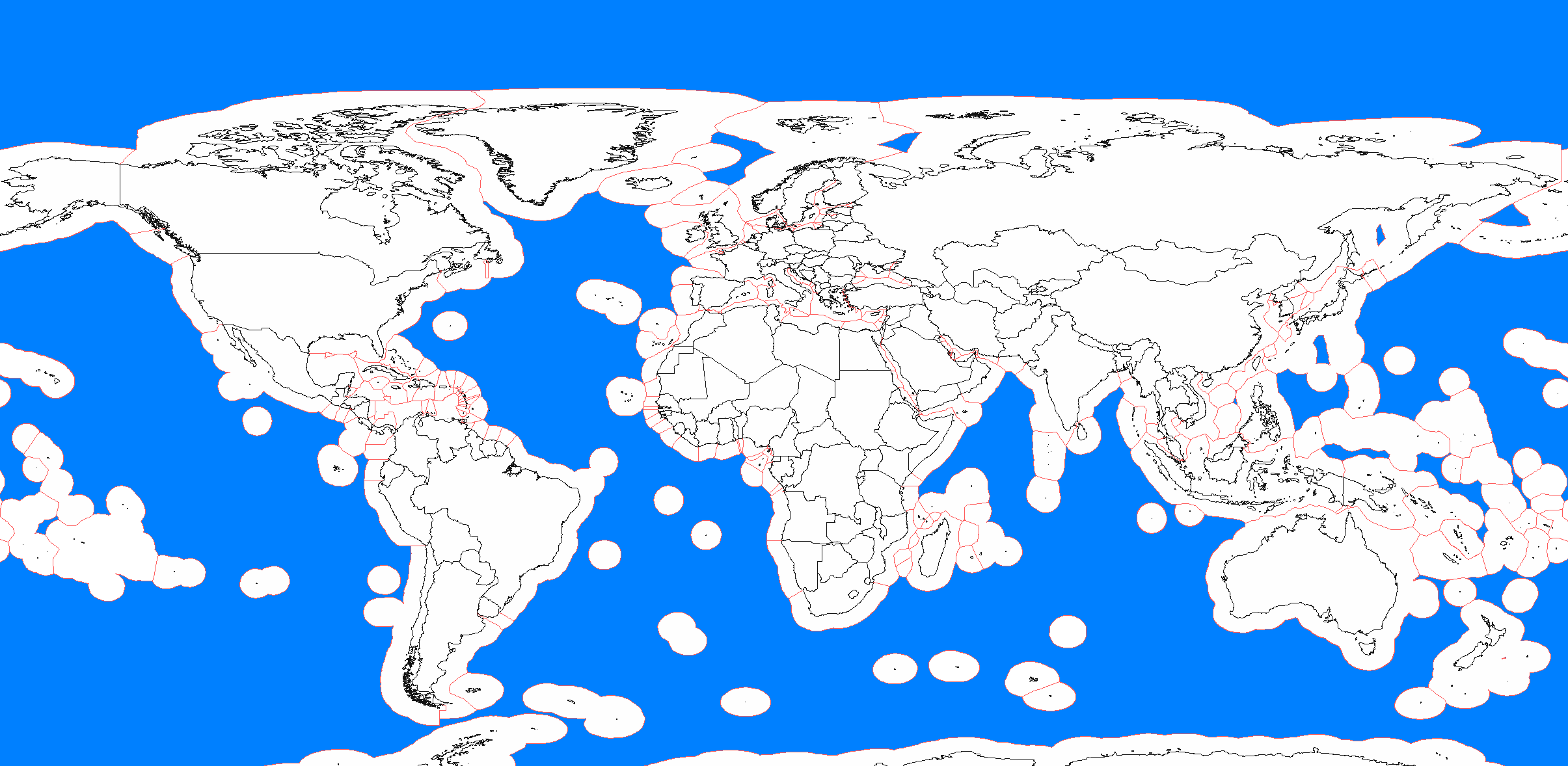

About half the ocean is found more than 200 nautical miles away from the shores of any nation, known as “the High Seas” or areas beyond national jurisdiction (ABNJ), where resources do not belong to any one country. Laws and regulations in these remote parts of the ocean have historically been scarce but are increasingly needed as humans have searched further and deeper for marine resources with growing demand and technological advances. Since World War II, Regional Fishery Management Organizations (RFMOs), such as the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT), have mostly been the sole environmental authorities on the High Seas, managing wildlife that transcend international borders and require collaborative, multi-lateral governance in order to be effectively managed.

But now there’s a new kid on the block…

After nearly 20 years of talks, governments at the United Nations finally agreed on March 4, 2023 to a new treaty for, “the conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity of areas beyond national jurisdiction”, known more commonly as the “BBNJ Treaty”. The BBNJ Treaty sets the legal framework to develop and implement area-based conservation in the High Seas, including marine protected areas (MPAs), where ocean uses (e.g., fishing, seabed mining, marine transit) could be restricted. This comes on the heels of the Convention of Biological Diversity’s COP15, where countries agreed to protect 30% of the ocean by 2030.

Several blogs, articles, and press releases have already reviewed the strengths and weaknesses of the BBNJ treaty for creating a network of effective MPAs in the High Seas. The treaty is a momentous step not only for the future of MPAs, but also for the RFMOs we frequently work with as the entry of a second form of conservation policy in managing marine resources on the High Seas. So we can’t help but wonder; How will different stakeholders in RFMO fisheries respond to the treaty? What are the implications for RFMOs and international fisheries at large? And ultimately, will the BBNJ treaty and RFMOs get along, or might they stand in each other’s way?

First and foremost, fisheries regulated under international law (i.e., managed by RFMOs) are exempt from the provisions in the treaty with respect to management of marine genetic resources where those provisions apply (e.g., genetic research on fish stocks). This inclusion makes it clear that the BBNJ treaty is not considered a replacement for or trying to replicate the work done by RFMOs. Furthermore, where proposed MPAs may have an impact on or overlap with RFMOs, there are provisions that make collaborating with RFMOs obligatory, among other opportunities for two-way communication between the BBNJ treaty and RFMOs.

Many stakeholders have responded positively to this language in the treaty. In a March 7 press release, Europeche (the EU’s leading fishing industry organization) complemented the measure for, “respecting and building on the success of fishery management,” while further elaborating that the BBNJ sector, “values the recognition of the great work that the RFMOs have been doing for decades in terms of fisheries management and environmental protection.” Indeed many RFMO stakeholders not only value the efforts for BBNJ to acknowledge the work of RFMOs, but may even see RFMOs as a precursor to – or even example for – environmental management on the High Seas under the BBNJ treaty.

Still, that does not mean that the treaty has been accepted by stakeholders without concern. In their press release, Javier Garat of Europeche concluded that, “Wasting energy and effort in reinterpreting or distorting the BBNJ agreement to try to overrule a robust fisheries management regime, developed over decades by RFMOs, would only serve as a deterrent and an excuse for its non-ratification.” The concerns are made clear. Even with balanced language included in the agreed upon treaty, such as that the agreement shall not, “undermine relevant legal instruments and frameworks and relevant global, regional, subregional and sectoral bodies” such as RFMOs, some fear that the treaty could be used to overpower RFMOs and be counterproductive to fisheries management.

Now where do we stand on the BBNJ treaty’s potential consequences for RFMOs, positive and negative? First, as we advocate for policy tools like harvest strategies to promote good ocean governance, any additional legal frameworks with the potential to ensure sustainable activities in the High Seas should be welcomed. We also believe that, if well-coordinated, the BBNJ treaty and RFMOs could be complementary, fitting together like two pieces of a jigsaw puzzle that would have a positive impact on life in the ocean that is greater than the sum of their parts.

Surely, with political commitments to protect 30% of the ocean, what happens in the remaining 70% is highly important for the wellbeing of biodiversity within MPAs. This is especially true for highly migratory species, including tunas, sharks, and billfish managed by tuna RFMOs that frequently transit between MPAs and waters fully open to fishing. MPAs in the high seas will require effective fisheries management from RFMOs, including from long-term policy tools like harvest strategies, which have increased the abundance of some highly exploited species at rates comparable with the best MPA success stories. The productive collaboration and coordination between MPAs and other forms of fisheries management will be instrumental to the outcomes of the BBNJ treaty.

In turn, RFMOs also have the potential to benefit from a well-managed network of offshore and High Seas MPAs. This could be through protection of key breeding areas or other habitats, as well as spillover from protected key locations for stock health. Demersal species managed by RFMOs may especially benefit. And while much uncertainty remains over the spillover benefits for highly migratory species, there has been increasing evidence of potential spillover effects for some species in specific regions. Furthermore, MPAs have the potential to indirectly benefit RFMO managed species by contributing to broader ecosystem stability and supporting other species that they rely on for prey or other ecosystem functions.

Effective collaboration and coordination with other environmental agencies will be critical in ensuring that both the BBNJ treaty and the RFMOs realize their conservation objectives. And that – an inclusive and participatory process – is perhaps one of the most important features that lead to a successful BBNJ treaty. This is not surprising, as transparency and stakeholder engagement is a central component of harvest strategy development, effective MPAs, and most any policy to secure a sustainable future for the ocean. Some High Seas MPAs will likely be multi-use, where some forms of fishing are permitted, and relationships with RFMOs will likely be important for managing fisheries within and outside of MPAs. And even if protecting 30% of the ocean is achieved, it will still need to benefit from the enforcement and compliance tools and processes that are being developed at the RFMO level. Ultimately, sustainable management of the remaining 70% through science-based policies including harvest strategies will be required to secure a healthy future for the ocean.

In conclusion, collaboration and coordination with fishery agencies and corresponding stakeholders will be instrumental to the successful adoption of the BBNJ treaty in September, and for any High Seas MPAs developed through this legal framework in the years to come. Care should be taken to ensure that fishery managers and other stakeholders continue to have a voice at the table.